Last week, UNC asked faculty to pause instruction on Friday, Oct. 9 in observance of World Mental Health Day, “creating a three-day weekend and allowing time for self-care.”

When I first heard the news, I couldn’t help but laugh. But the laughter quickly subsided, creating space for anger. Putting other problems with the decision aside, the University’s assertion that it actually cares about the mental health of its students is gaslighting at its worst.

Actions speak louder than words — and the University has made it crystal clear that it doesn’t consider the well-being of students a priority. It never has.

Sexual assault has long been an epidemic on UNC’s campus, and the administration has done little to address it. Black students constantly fear for their safety because UNC’s incestuous relationship with white supremacy puts them in danger. This semester, the administration risked our lives in an experiment, jerking us to and fro as they tried (and failed) to carry out a successful reopening.

Student mental health was a concern long before COVID-19 hit, and it won’t disappear whenever things go back to “normal,” either. In 2019, the UNC Mental Health Task Force delivered its report to the Board of Trustees. The report cited data from the American College Health Association’s fall 2017 survey of undergraduate students, which found that in the year prior, 90 percent of undergraduate students reported feeling overwhelmed, 37 percent felt so depressed it was difficult to function and 1.3 percent — more than 245 individual students — had attempted suicide.

Yet mental health resources for students are woefully lacking. Campus and Psychological Services is perennially underfunded, with little representation for Black students and other students of color. Sexual assault victims rarely, if ever, see justice. And the University’s approved absence policy effectively punishes those whose struggles do not fall under the categories of absences the administration has deemed excusable.

The task force issued a number of recommendations in its report, including the creation of a permanent committee on mental health, increasing accessibility to vital mental health services and diversifying counseling staff. That was nearly a year and a half ago. What has the University done since to provide a lifeline to students?

Here’s what caring about mental health is not: upholding a legacy of institutional racism. Underinvesting in psychological resources for students. Shifting the responsibility of student mental health to professors, many of whom are already doing more than the University ever has to support their students. Implementing an attendance policy that provides no room for emotional struggle and forces students to divulge our pain in order to heal.

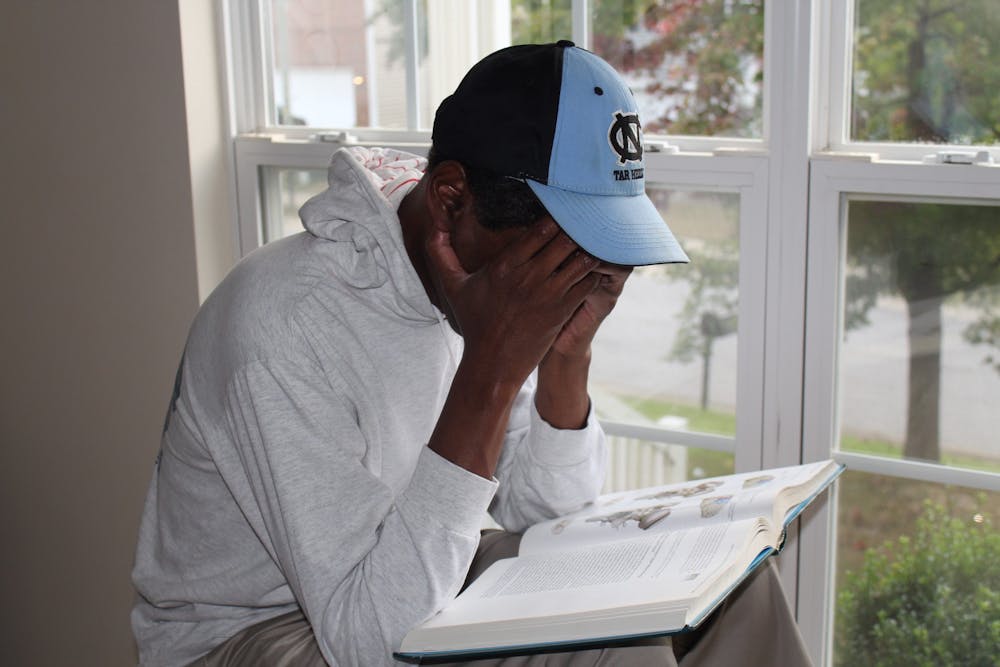

Students are drowning, struggling to stay afloat. We are relieved when the administration finally throws us a life raft, only to find that it is out of air. That is what this feels like — trying to keep our head above water with nothing but a deflated life raft to cling to.