In the same email, Stahlman said someone reached out to a poster asking to look into the situation more.

"In the meantime, I'm monitoring the page overall," Stahlman wrote.

In an interview with the DTH, Stahlman said she thinks students deserve their own spaces to talk about whatever they want.

“I really value that, and I would never intentionally infiltrate a space where I wasn’t wanted or where my identity doesn’t fit the parameters of the group," she said. "I also really value listening and supporting students when I can. But I also understand that in such a large group, it’s really hard for folks to know who all the members are.”

In response to an interview request, Pittman sent a statement.

He said a few years ago, Campus Health leadership recognized that feedback from patient surveys was valuable but did not completely represent students’ positive and negative experiences.

“Campus Health Advisory Board recommended we review the Facebook group as part of our performance improvement efforts and as a supplement to our existing patient surveys and feedback mechanisms,” Pittman said in the statement.

As recently as February 2020, CHS employees were discussing what students posted on the page.

Stahlman joined Babes Who Blade about one year after the group was created when someone emailed her saying they “had seen some inflammatory comments on Facebook pages.”

Stahlman wrote back to the sender, whose information was redacted in the public record, thanking them for letting her know about the group.

“I don't have a way to monitor groups like Babes Who Blade… nor to even know they exist beyond folks like you letting us know. I do have alerts set for news mentions of us, but google doesn't track private groups. Do you know of a way to monitor them?” she wrote.

In the statement, Pittman said negative feedback from students was incorporated into Campus Health's performance improvement and assessment process, and sometimes shared with the specific provider. Positive feedback was also passed along to the provider, but in neither case would they share identifiable information about the poster.

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

Stahlman got into the group the same way as every other member, by answering three intake questions: Why do you want to join, what is your gender identity and do you agree to follow the rules of the group.

Stahlman said she remembers answering that she wanted to join in order to help improve student experiences — while disclosing that she is a CHS employee.

“I would never have hidden that," she said.

Maguire said administrators only deny member requests if the person answers “no” to group rules or if they identify as a cisgender man.

“It doesn’t really matter what you say for why you want to join the group,” she said.

In the past, Stahlman commented on posts giving advice about things not related to UNC or health care. Pittman said in a statement that Stahlman disclosed that she is a staff member when interacting in the group.

She said now that she’s been using the two groups for four years, she doesn’t use it the same way as she had in the past.

“I think over time I’ve gotten comfortable, and I’ve started interacting with the group just as myself,” Stahlman said.

Babes who Blade origin

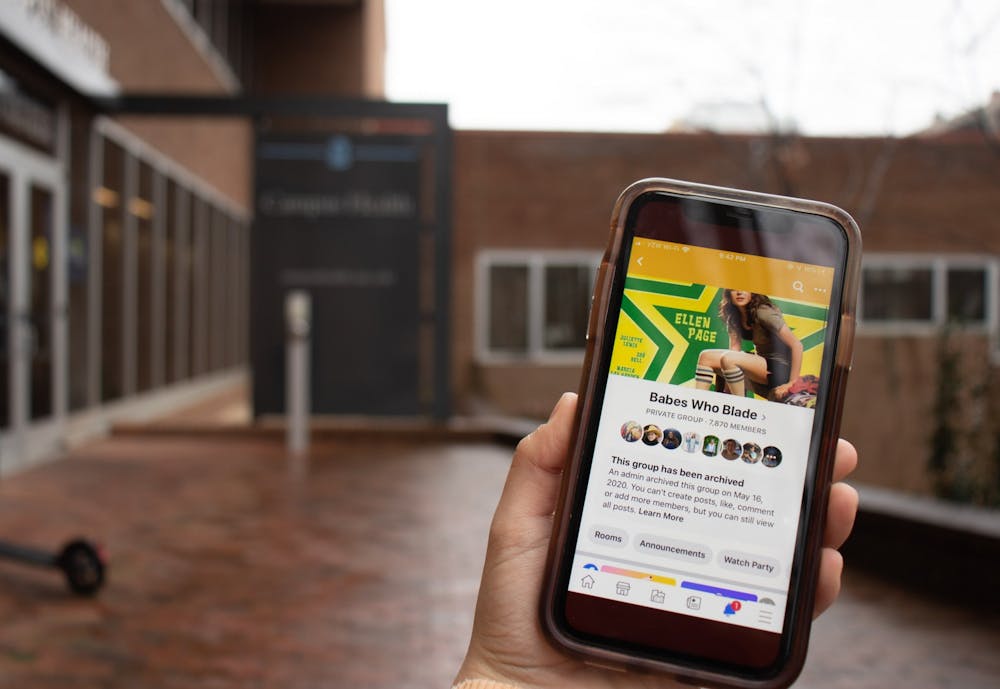

At its origin, Babes who Blade connected a group of friends at UNC interested in rollerblading. But it soon grew to include more than 7,000 users, most of them UNC students.

People in Babes Who Blade would ask and give advice on a wide range of topics — same as they do in its reincarnation, Bagels Who Discuss. One requirement for entry to the group, same as Bagels, was that members’ gender identity was not cisgender male.

The group devolved into what some observed as a problematic landscape. People of color described demands for emotional labor by cisgender white women.

“One of the things that I know was really frustrating in Babes Who Blade was that a lot of marginalized people, such as people of color, queer people, having to re-explain their oppression to straight people and white people, about, like, ‘Hey, here’s why it’s inappropriate for you to do this,’” Maguire said.

Bagels Who Discuss set out to be more inclusive than Babes Who Blade.

In an email in May 2020, Pittman discussed the demise of Babes Who Blade and said: "Will likely materialize as another replacement group and we will monitor."

Digital privacy

One rule for members in Bagels Who Discuss is that if anyone wants to share posts outside the group, they must ask the original poster for permission.

“But at the same time, we know that this is the internet,” Maguire said. “It is a private Facebook group, so obviously people that aren’t in the group can’t see the posts, but that is to say that we can’t monitor all 4,000 people that are in the group from sharing content elsewhere.”

She added that if any administrators or moderators find out that anyone has shared content outside of the group and it’s been harmful to a member, it would be grounds for removal from the group. That has happened once since the group formed in May 2020.

Stahlman said she has not shared any screenshots, but would convey themes and an overall sense of CHS services.

“Any time I’m passing along information, it would be de-identified and aggregate with that goal to improve student experiences,” she said.

Anne Klinefelter is a law professor at UNC specializing in digital media and privacy. Considering the situation, she said CHS monitoring what students said about them could be considered best practice for a business.

“Businesses absolutely want to see what’s being said about them in all sorts of places online. Some would say it's just responsible stewardship and actually responsive to those they serve,” she said.

Klinefelter said that privacy is not the norm online, even in a group that is termed “private.” In this situation, she said, more than just CHS could be monitoring the discussion.

“Anybody who’s in there could be taking this information and doing something with it that somebody there finds offensive,” she said. “Most people really don’t take time to read the terms of service, and they just generally don’t choose privacy over convenience or connection or information access.”

Klinefelter said when looking at the ethics of a situation such as this private group, she looks at two stages. One is access — the group administrators admitted Stahlman. The other is what Stahlman or any other admitted member does with the information shared in the group.

“Particularly if you have groups that feel marginalized, they might feel fearful of taking concerns directly to a more powerful entity and just want to figure out a way to work the system without trying to confront the system,” she said. “If a service provider were really acting in an ethical way, they might want to try to know these concerns so that they can address them. There are some potentially good ways of doing this.”

@elizltmoore

university@dailytarheel.com