In 1948, McKissick applied to UNC School of Law but was denied solely because of his race.

It was during his time at NCC that the NAACP, led by Thurgood Marshall, decided to take up his case against UNC. After the ruling, McKissick enrolled in the summer session and took one class at UNC as a symbolic measure.

Following law school, McKissick established a law firm that handled civil rights issues in Durham, becoming a prominent member of the civil rights movement. His heavy involvement with the Congress of Racial Equality and the NAACP led McKissick to be named the head of CORE in 1966.

Harvey Beech

Beech’s father, who was a barber, had the same aspirations for his son. Instead, Beech defied his father’s wishes and attended Morehouse College, where he was captain of the football team and a classmate of Martin Luther King, Jr.

At UNC, Beech faced constant discrimination. A stroll on campus would likely confront him with the segregated water fountains and the glares from white students. Once, the chancellor offered Beech a football ticket, but told him he’d have to sit behind the goalposts in the African American section.

Beech fired back, “If you give me a ticket, I’m gonna sit where I damn want.”

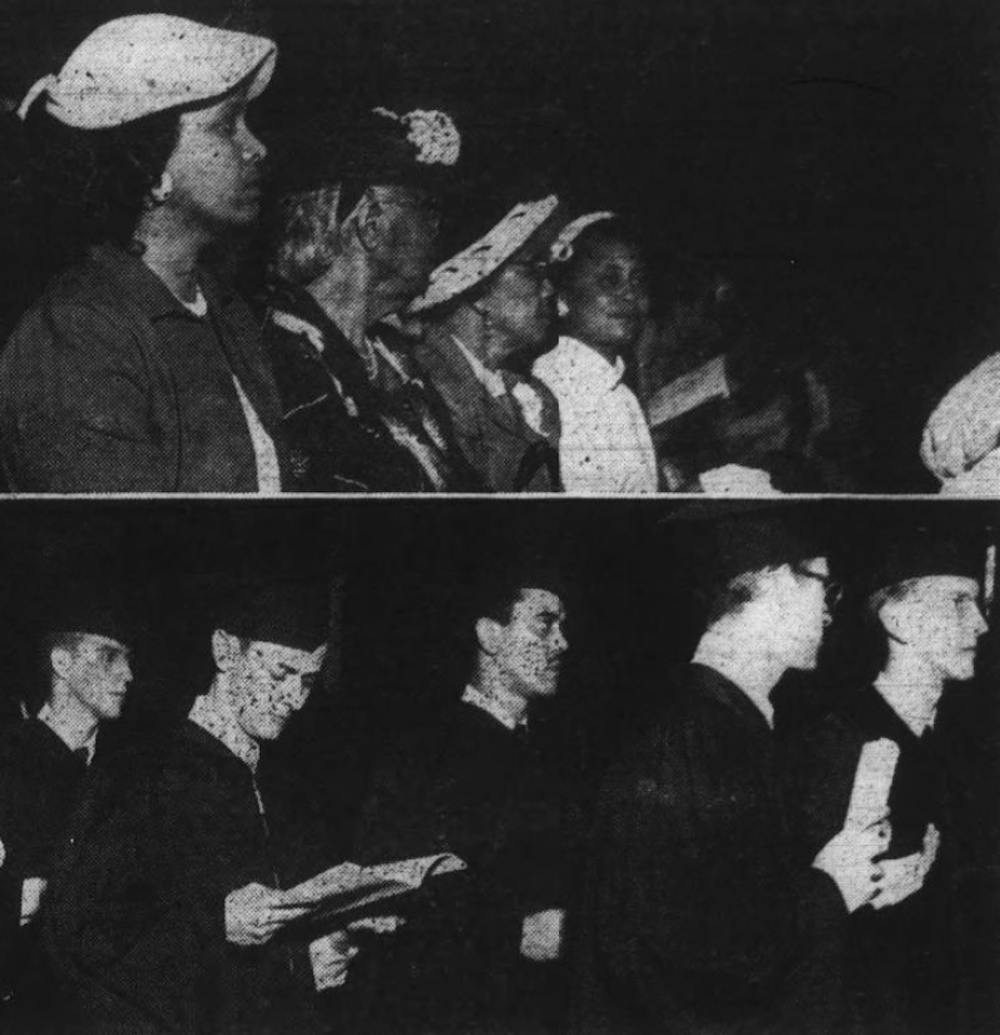

Yet Beech also recognized those who helped dissolve the racial barrier at UNC. He would often speak of the white editor of the Carolina Law Review, who stepped out of line so he could ensure that Beech wouldn’t walk alone at graduation.

Speaking at Beech’s graduation, North Carolina Gov. Kerr Scott stated, “Never in my life have I seen so many intelligent people sitting in the dark. Things are changing. Get ready.”

After graduation from UNC, Beech resided in Kinston, practicing law for 35 years while keeping his UNC ties strong.

Beech was awarded the William Richardson Davie Award, the highest honor given by the Board of Trustees. Today, several awards in the Black Alumni Reunion are named in his honor.

J. Kenneth Lee

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

Lee, the grandson of slaves, was an accomplished World War II veteran. One of the main reasons he chose UNC was because he knew he wasn’t welcomed. In the News & Observer, Lee detailed the threats he and the other students received for their enrollment.

When the five men enrolled, people threatened the law school, preferring for it to shut down rather than teach black students. The threats became so violent that the students had to isolate themselves in a dorm.

After completing his degree at UNC, Lee became a civil rights attorney in Greensboro, where he went on to represent a majority of the 1,700 civil disobedience cases in North Carolina resulting from the Woolworth sit-ins.

James Lassiter

Lassiter ended up transferring and graduating from North Carolina College School of Law after a brief stint at UNC. However, Lassiter was just beginning to break race barriers at UNC. After his law school career, he was named the first African American to be a field agent for the United States Department of Commerce.

James Robert Walker

During Walker’s time on campus, he fought to participate in normal campus life. Even after enrollment, campus activities remained either closed to African Americans or strictly segregated.

After the BOT and the chancellor denied Walker access to the University's traditional spring dance, Walker responded with a letter stating, “I will never accept the denial of a privilege. I have made footprints around the world defending a free society.”

In addition to practicing law, Walker advocated to abolish the voter literacy test and end voter suppression in several rural, predominantly African American counties across North Carolina.

As we celebrate Black History Month and honor the first African American students to enroll at UNC, let us not forget the many hardships they experienced. Let us celebrate the grit and determination required to overcome the prejudice that these men faced.

Finally, let us remember the paths that these men paved for students of any background to not only attend, but create a legacy at UNC.

And about that swimming pool pass, Beech never gave it back. He told them he was going swimming if he wanted.

@dthopinion

opinion@dailytarheel.com