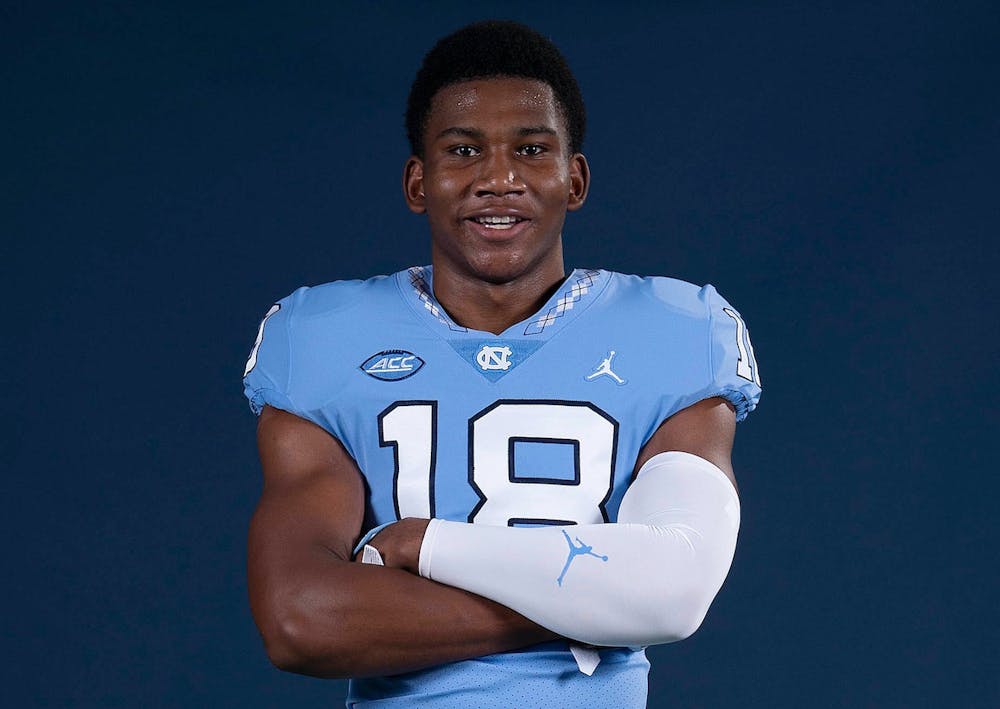

Christopher Holliday is the heir to two distinct, important legacies.

His father, Corey Holliday, was a wide receiver on the UNC football team from 1989-1993, with his 2,447 receiving yards while playing under head coach Mack Brown placing him fourth on UNC’s all-time receiving yards list. The younger Holliday has fulfilled this legacy by coming to UNC as both a Morehead-Cain Scholar and a walk-on defensive back on the football team, playing under the same coach as his father.

The second one may be harder to pick up at first glance, but it's just as powerful. Holliday’s maternal grandfather is Harvey Gantt, the first Black student to gain acceptance to Clemson University and the first Black mayor of Charlotte, N.C. Holliday’s grandmother and Harvey’s wife, Lucinda, was the first Black woman accepted to Clemson. By just coming to UNC and seeking an education, Holliday is fulfilling that legacy.

“(Gantt) has always instilled education as the biggest priority in our family because that’s what’s able to separate many African Americans,” Holliday said. “They’re disproportionately disadvantaged in many of the situations they begin in, and education can help them rise to reach the greatest successes possible.”

Gantt gained national prominence when he challenged longtime Republican incumbent and staunch segregationist Jesse Helms in the 1990 North Carolina Senate election. He was the target of the now-infamous “White Hands” advertisement, in which Helms’ campaign claimed that Gantt supported racial quotas that would see supposedly underqualified Black workers hired for jobs over white people with greater qualifications. Gantt would go on to narrowly lose that election.

“(Helms was) someone who was accused of having disdain for the Black community, and I would say that he did have disdain for the Black community,” UNC history professor Matt Andrews said. “And then here comes this young Black politician, the mayor of Charlotte, and he kind of became the hope of progressives all around the country.”

And yet, as a kid, Christopher didn’t see Gantt as the ground-breaker and pillar of progress that much of America saw him as. To him, he was just granddad. It was only when he went to the opening of the Harvey B. Gantt Center in Charlotte in 2009 that he began to realize the scope of what his grandfather had done.

“I did not know any of that,” Holliday said. “You’re such a young kid, so you just see him as this hero for a different reason, when everybody else sees him as a hero because he was able to set so many trails.”

But knowing all that doesn’t change the fact that, to Holliday, Gantt is still granddad. Holliday said he calls him almost weekly, with topics of discussion ranging from school, life and sports — despite his son-in-law and grandson, Gantt is still a diehard Clemson fan — to the ongoing racial justice movement in the United States. Gantt was proud to see masses of people take a stand for an issue to which he’s dedicated his whole life, his grandson said.