Watts described her recruitment by longtime UNC head coach and national champion Sylvia Hatchell as “a blessing.” When she arrived on campus she fell in love with Chapel Hill: the student body, the constant energy of Franklin Street, the hallowed Carmichael Arena where she practiced and played.

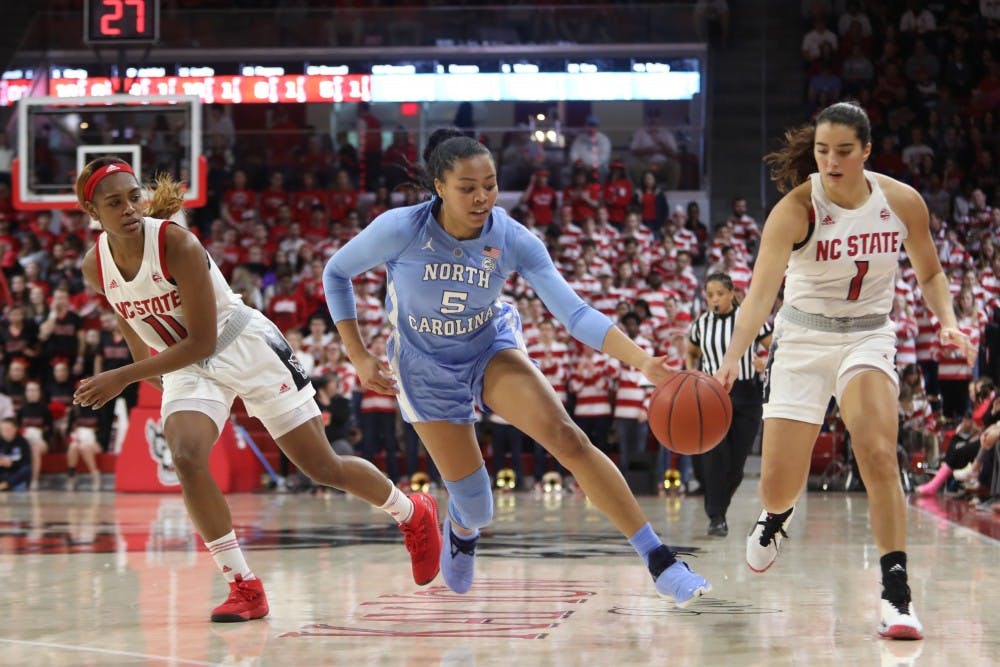

Her first two seasons, individually at least, were just as divine. Though the Tar Heels went 14-18 in 2015-16, Watts set a UNC first-year record with 76 made 3-pointers and she was named ACC Freshman of the Year.

As a sophomore, Watts set an ACC record with 10 made triples against Charleston Southern and finished top 10 in the conference in points, minutes, rebounds, blocks and steals. But she missed the final five games of the season thanks to injury, the same injury that kept her out for all of 2017-18.

Still, Watts seemed intent on finishing out her career in Chapel Hill. For the first time since her arrival, North Carolina made the NCAA Tournament in her redshirt junior year, albeit losing to California in the first round.

From the outside looking in, things were trending up, and Watts would enter her final season with a chance to leave a legacy on both team and individual levels.

Then, the investigation happened.

A program in flux

On April 4, 2019, the Washington Post published a story with allegations that Hatchell made a series of offensive comments, including one suggesting her players would get “hanged from trees with nooses” if their performance didn’t improve.

The Post story also included allegations from parents that Hatchell pressured multiple Tar Heels to play through injury; in one instance, an unnamed player found out she’d suffered a torn tendon in her knee, presumably after a team doctor told her otherwise.

Two weeks later, Hatchell resigned, leaving a program that had had the same head coach since 1986 in flux.

A handful of players transferred elsewhere. Among those transfers was Watts, the girl who’d suffered her own knee injury amid accusations of injury mismanagement; the girl who’d fallen in love with UNC and was now left wondering how much it loved her back.

“It was definitely tough,” she said. “But I think one of the biggest factors that went into it wasn’t even basketball, honestly.”

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

Watts said that the program’s uncertainty aside, she was ready for a change of scenery. A public policy degree in hand, she started looking for grad school programs she could finish in one year, in places she would want to live. She decided on USC, setting her sights on a master’s in entrepreneurship and innovation.

“It wasn’t a dissatisfaction with North Carolina,” Stephen said. “It was just an opportunity to try and do something different.”

But it wasn’t long before Stephanie’s California sojourn turned sour. Watts played exactly four games with the Trojans before finding out she had a cyst in her knee that needed surgery. She spent the next few months in rehab before COVID-19 hit the United States, prematurely leaving Watts with a lot of time to think about her future.

Because of the injury, she’d have another year of eligibility, another chance to end her college career on the right note.

"(USC) was a beautiful place to be, I had a great experience," she said. "But after I got hurt there, going through another injury, I just wanted to go back home.”

'Just following my heart'

In spring 2019, before she ever departed Chapel Hill for greener pastures, Watts was getting shots up in Carmichael Arena when she was approached by a new face.

It was Banghart, the former Princeton head coach who’d just been tasked with rebuilding North Carolina women’s basketball. The two exchanged pleasantries, and Banghart told Watts that even though she was transferring, she’d always be welcome back as an alum of the program.

“I was so conflicted,” she said. “Like, ‘Wow, she seems like such a great person, and I would love to play for a coach like her.’ But I’m like, ‘Geez, I already kind of made up my mind.’”

Watts kept those few interactions with Banghart in mind when it came time to leave USC a year later. When Watts entered the transfer portal, Joanne Aluka-White, a Tar Heel assistant who recruited Watts when she coached at UNC-Charlotte, put her in contact with Banghart, who wasn’t immediately sure what to make of the situation.

“I didn’t really actively recruit her back, because I didn’t know what I was really getting into,” Banghart said. “I didn’t know much about her. Was she a part of the tumultuousness (of the past regime) or not?”

With some questions lingering, Watts did her due diligence exploring other options, with the most serious contender being Syracuse. As she mulled her options, she called her dad, and they agreed that playing for the Orange would be a great opportunity. She decided to sleep on it. Watts woke up in the middle of that night, still thinking over one of the biggest decisions of her career.

The next morning, though, she called her dad and told him she’d made up her mind: she wanted to return to North Carolina.

It was just an instinct she had, she told him, a feeling that she needed to go home.

Stephen told her he’d had the same feeling all night long.

“After I got off the phone, my gut just kept telling me, ‘She needs to go back to Carolina,’” he said.

The legacy of Watts, one of the most talented players in North Carolina history, is a complicated one. Some will mention her 3-point records; others, her all-around game. Coaches point to her tenacity battling back from injury, while teammates know her as a beacon of positivity.

Above all, though, Stephanie Watts will be remembered as the woman who left Chapel Hill to find herself and couldn’t do it until she returned back where it all started.

Home.

“I think it was me just following my heart, really,” she said. “It didn’t feel right to finish my career anywhere but UNC.”

@ryantwilcox

@dthsports | sports@dailytarheel.com