Carrington’s father was an electrical engineer and her mother was a labor and delivery nurse who struggled with a bipolar disorder.

Carrington began having mental health and self-esteem issues when she was a teenager. But she graduated in the top 10 percent of her high school class. She attended UNC and majored in Spanish with a double minor in English and psychology.

“I ended up having a domestic violence situation that didn’t allow for me to finish college,” Carrington said, having to leave school with only one semester to go.

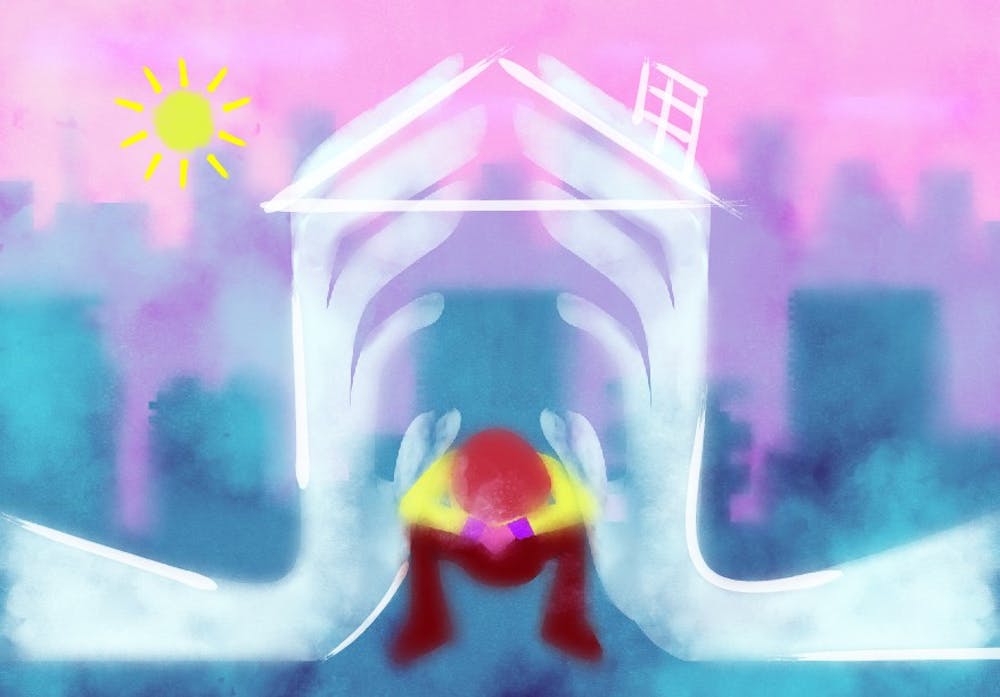

She married, had children, but split from her ex-husband. That was accompanied by her increasing dissociation with reality — something she feels was a big factor in her family becoming homeless.

“In my anxious brain, I can worry a problem to death, but be paralyzed to do anything about it,” she said. “Also, mental health affects how you feel about who you are sometimes to the point where you don’t care about yourself at all. The skill I used to compensate was spending money.”

Then, in 2002, came the moment she’ll never forget, getting locked out of her apartment, unsure of where to go, with an 8, 7 and 1-year old.

With their clothes and confusion as their only remaining possessions, Carrington and her children moved into the Durham Rescue Mission. Her natural intellectual ability allowed her to get a job in data entry with the organization.

“I think about a lot of times this perception people have of people that are homeless. I was a smart person, that was not my problem,” Carrington said. “It was systems and circumstances around me and having mental illness that changed the trajectory of what I was doing.”

She eventually moved her family out of the Rescue Mission, but in 2013, years later, it was happening again.

The single mother had found herself jobless because she was charged with larceny. She said she didn’t do it, but lawyers were a luxury she couldn’t afford.

Though affordable housing is defined as costing 30 percent of a person’s income, Carrington’s Chapel Hill apartment was costing her 80 to 90 percent of her income. These factors were compounded by the expenses of raising a high school senior.

Putting on a brave face this time around was harder for Carrington than when her children were younger. Crowded around a table at McDonald’s eating breakfast, her kids looked at her wide-eyed.

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

“I had no other plan. I knew I didn’t have enough money to find another place…I was scared, angry at myself for getting me in this predicament,” Carrington said. “My children were very quiet, scared and watching me.”

That’s when Carrington got a call that a space had opened up for them at the homeless shelter in Chapel Hill.

“Even when you go into the shelters, you know, the type of shelter is great, it’s clean, you have your own room or bathroom as families, but it’s still not home,” Carrington said. “I think people don’t understand how stressful that is to try to make all of that look normal, like it’s supposed to be.”

In 2014, Carrington was able to move into her own place in Chapel Hill and started working as a savings assistant part time for the organization she now leads.

Maggie West, who served as CEF’s co-director from 2009 until 2018, reflected on when she first hired Carrington, laughing when she confessed to only interviewing her for the position.

“I think the things that have always stuck out to me about Donna is just how clear and passionate she is as a communicator,” West said. “She was always able to do that, the really hard work of making people feel heard while also helping them take that next step, whatever that may be.”

In 2018, CEF came up with a strategic plan to be more racially equitable, identifying one of its goals as having a Black co-director. Already doing the workload of the position, Carrington interviewed for it and come March 16, will have been executive director of CEF for a year.

“CEF is a very heart-filled place and has always been led by the heart and I think Donna as a person has always led with her heart,” West said.

In 2019 alone, Community Empowerment Fund helped divert 45 households in Durham and Orange counties from homelessness. Carrington is focusing on how CEF can address the impacts of systemic racism on Black and Brown community members, recognizing that in 2020 in Orange County, 49 percent of the homeless population was Black, while they make up only 12 percent of the general population.

Corey Root, the Orange County homeless programs coordinator for the Orange County Partnership to End Homelessness, said she has seen the need for homelessness services sky-rocket since the pandemic.

Their various services used to assist around about 16 people per month, now it is not uncommon to serve one hundred people per day, with more than 70 more people on their list waiting for housing.

Carrington hopes to see Orange and Durham counties make a renewed effort to find creative housing solutions, have more collaboration with more landlords and enhance understanding from community members.

Her experience with homelessness has given her scars, but has also taught her valuable lessons.

“I have the beautifulness of being a person of lived experience and running an organization,” Carrington said. “So being able to be that voice in the room and know that I’m representing lots of people — that’s great for me.”

@DTHCityState | city@dailytarheel.com