“So… what are you doing this summer?”

This question is universally dreaded by college students, who face a competitive internship market — even more so in a pandemic.

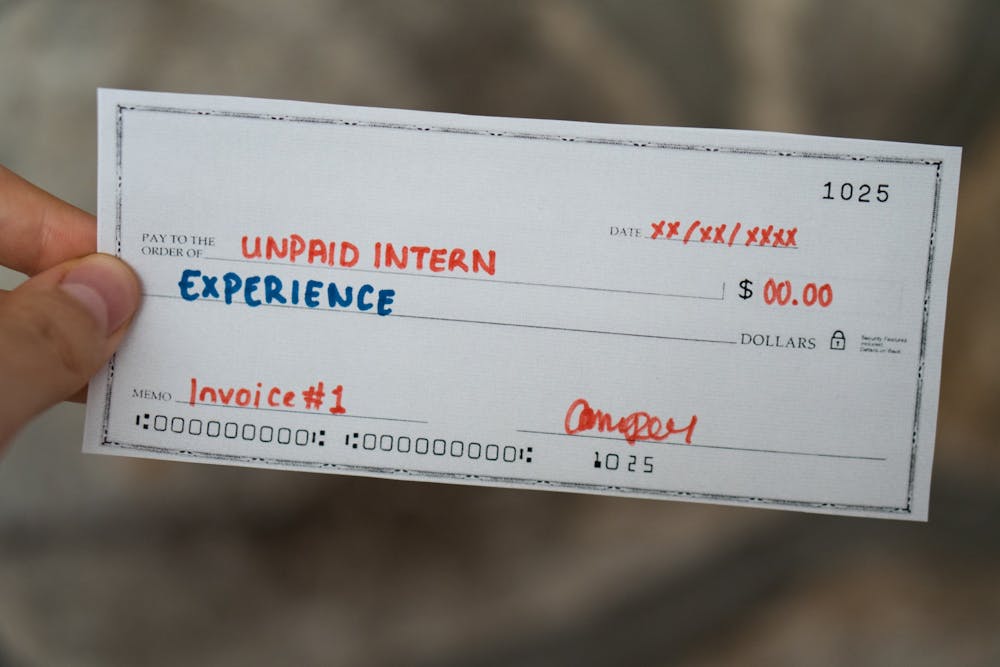

The internship search forces us to examine our priorities. Should we choose an unpaid job doing something we love, or a paid position in a less relevant field?

The debate over unpaid internships is not new, but it resurfaced recently after Jane Slater, a reporter for the NFL Network, tweeted in support of unpaid internships, saying, "There is a reason not everyone makes it in this business. I don’t have time for those of you who don’t understand grind."

Many Twitter users pointed out the privilege behind her statement. Unpaid internships are inherently problematic, they argued.

But unpaid internships still remain remarkably prevalent. According to a 2018 survey from the National Association of Colleges and Employers, some 43 percent of internships at for-profit companies are unpaid.

In a country permeated by worsening income inequality, unpaid internships are a gatekeeper for low and middle-income students, who simply do not have the luxury of working for free. Unpaid internships exploit the labor of college students and exacerbate existing inequalities in the corporate world.

How unpaid internships work

Under the Fair Labor Standards Act, for-profit employers must pay employees for their work. However, interns and students are not necessarily considered employees under the FLSA, and therefore do not require compensation.

In the U.S., unpaid internships are legal as long as they meet certain criteria. In January 2018, the Department of Labor released updated guidelines to determine whether or not an intern or student is an employee under the FLSA.

This test, known as the “primary beneficiary test,” has seven parts. The general rule of thumb is that the intern must benefit more from the internship than the company hiring them.

However, some say the new standard has made hiring unpaid interns easier by removing a previous rule that interns could provide no “immediate advantage” to the company.

It’s not just pay that interns are losing out on. Because they are not technically considered employees, unpaid interns do not receive benefits or protection against workplace harassment and discrimination in most states.

All work, no pay

Internships have become almost necessary for future success — studies have shown that students graduating with internship experience are more likely to find employment upon graduation.

Simon Palmore, a sophomore majoring in history and Hispanic literatures and cultures, worked full-time in an unpaid role for a congressional campaign from May to November of last year. He spent seven days a week helping with the campaign, while also juggling school, a social life and his own well-being.

“It stretched me just about as far as I could go, and I kind of had to sacrifice certain things,” Palmore said. “I don’t know if I anticipated how taxing it would be beforehand.”

Political campaigns, such as the one Palmore worked for, rely heavily on unpaid student labor. Fortunately for Palmore, he was able to accept an unpaid position — he had financial support from his parents, so he didn’t have to pick up a part-time job to make ends meet.

However, not everyone has the same luxury. One study from the University of Wisconsin found that 64 percent of students who did not take an internship had desired to do so, but could not due to scheduling conflicts with work, insufficient pay and lack of placements in their disciplines.

Caryl Espinoza Jaen, a sophomore majoring in English at N.C. State University, is an international student. His current visa does not make him eligible to work in the U.S., so all of the work he does is on an unpaid basis — even when his colleagues are paid.

“I like to joke about it to my colleagues,” Espinoza Jaen said. “Sometimes stupid shit happens, and I’ll be like, ‘You know, I don’t get paid enough for this.’”

Those who defend unpaid internships argue that such opportunities provide students with valuable experience and exposure. But experience and exposure don’t pay the bills, particularly if you don’t have parents or family members who can afford to subsidize your living costs. Many major U.S. cities like New York and Washington, D.C. are prohibitively expensive, especially when you’re not getting paid.

“How are you going to do that unless you have somebody to depend on who has the money for it?” Espinoza Jaen said. “It just gatekeeps a lot of low-income and even middle-income folks.”

Exacerbating inequalities

Internships are largely about who you know. But perhaps the bigger question is: how do you know them?

Wealthier students tend to have larger professional networks and mentors who can connect them with paid opportunities — a disparity that LinkedIn CEO Jeff Weiner has dubbed the “network gap.”

If you grew up privileged, you’re more likely to attend an elite college and have industry connections. Students with these resources land better internships. Prestigious internships are a gateway to successful careers. The cycle goes on.

And it’s students of color who are disadvantaged the most, overrepresented in unpaid internships and underrepresented in paid ones. Data from the 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances show that the typical white family has eight times the wealth of the typical Black family and five times the wealth of the typical Hispanic family.

As a result, unpaid internships perpetuate existing inequalities, contributing heavily to a system in which access and opportunity go to those who already have plenty of both.

Rishabh Patel, a junior majoring in exercise and sport science and economics, said he feels he has no choice but to accept unpaid internships due to a lack of familial connections — it’s the only way he can get his foot in the door.

“I’m a first-generation college student, my parents immigrated to this country,” Patel said. “Everything that I have to do, I have to network and do it myself, because I’m going into an industry where there's not many people that look like me.”

Closing the gap

When we consider how unpaid internships make many careers inaccessible, it’s really no surprise that industries like journalism and the arts are overwhelmingly white. The lack of diverse voices in these fields is a disservice to everyone, yet we continue to shut them out of the conversation.

The Daily Tar Heel, too, relies largely on unpaid or underpaid labor from its reporting staff and editors. As a result, our staff isn’t nearly as diverse as it should be.

An internal diversity audit conducted last semester confirmed what many have always known — the DTH is a predominantly white, upper-class newsroom. Almost a third of the staff has a family income of above $150,000, and nearly a quarter has a family income between $100,000 and $149,999.

While the onus does lie on employers to start paying their interns, colleges and universities must step up to support students, too.

Initiatives like UNC’s Carolina Covenant and the DTH’s Sharif Durhams Leadership Program aim to provide underrepresented and low-income students with mentoring and access to professional opportunities.

Experience is valuable, and internships certainly give students a leg to stand on. But at a time when students face a record $1.6 trillion in student loan debt, unpaid internships don’t seem like the solution.

Most people cannot afford to work for free, and they shouldn’t have to. Colleges and employers should invest in opportunities that dismantle systems of oppression — not perpetuate them.

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.