At 50 years old, Keith Edwards could still recall crying after her first day of seventh grade at Chapel Hill Junior High School.

Chapel Hill-Carrboro City Schools had begun desegregating, so Edwards could not attend Lincoln High School, an all-Black school in the district that she thought of as a cocoon.

“I ended up coming out as a butterfly with weakened wings," she told Robert Gilgor, a local documentarian, during an interview with UNC’s Southern Oral History Program in 2000. "I didn’t have enough room to fly when I went to an all-white school.”

This year marks 60 years since desegregation began in CHCCS. But even now, across the district’s 20 schools, white students access more opportunity and face less discipline than Black students, according to a Daily Tar Heel analysis of the most recently available federal, state and local data.

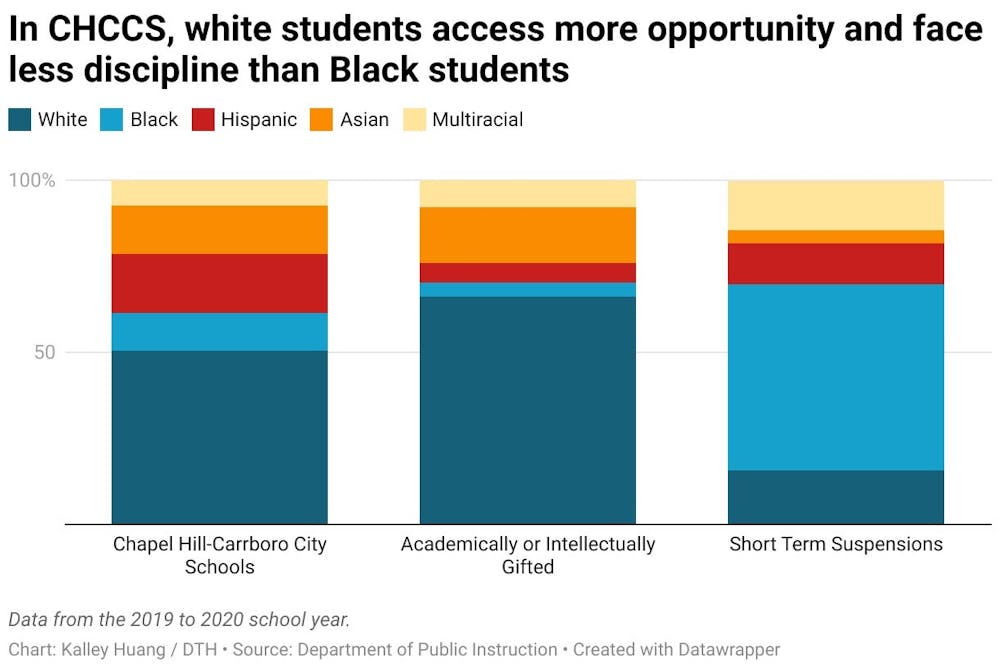

During the 2019-20 school year, about half of all CHCCS students were white, 10.9 percent were Black, 17.3 percent were Hispanic, 13.9 percent were Asian and 7.3 percent were multiracial, according to data from the Department of Public Instruction.

But last school year, white students in the district were 3.5 times more likely to be identified as academically or intellectually gifted — a designation that allows access to more advanced and specialized instruction — than their Black peers, while Black students in the district were 15.8 times more likely to be suspended than their white peers.

Statewide, white children were 3.7 times more likely to be in a gifted program than their Black peers. Black children were four times more likely to be suspended than their white peers.

“It’s commonly said that (Chapel Hill) has the second largest achievement gap in the country,” Jeff Nash, executive director of community relations for CHCCS, said. “It’s unacceptable, and we’ve known that. We’ve been working on it.”

Nash said steps to address the district’s racial disparities include developing a strategic plan, which would generate the district’s priorities and goals by “including a very diverse group of people from our community." He also said CHCCS plans to conduct an equity audit.