The late 1960s were characterized by an upswell of civil strife across the world.

Anti-war and racial justice protests filled the streets across the United States. Abroad, students occupied public buildings across Paris and anti-authoritarian demonstrations exploded in Mexico, Czechoslovakia, Pakistan and elsewhere.

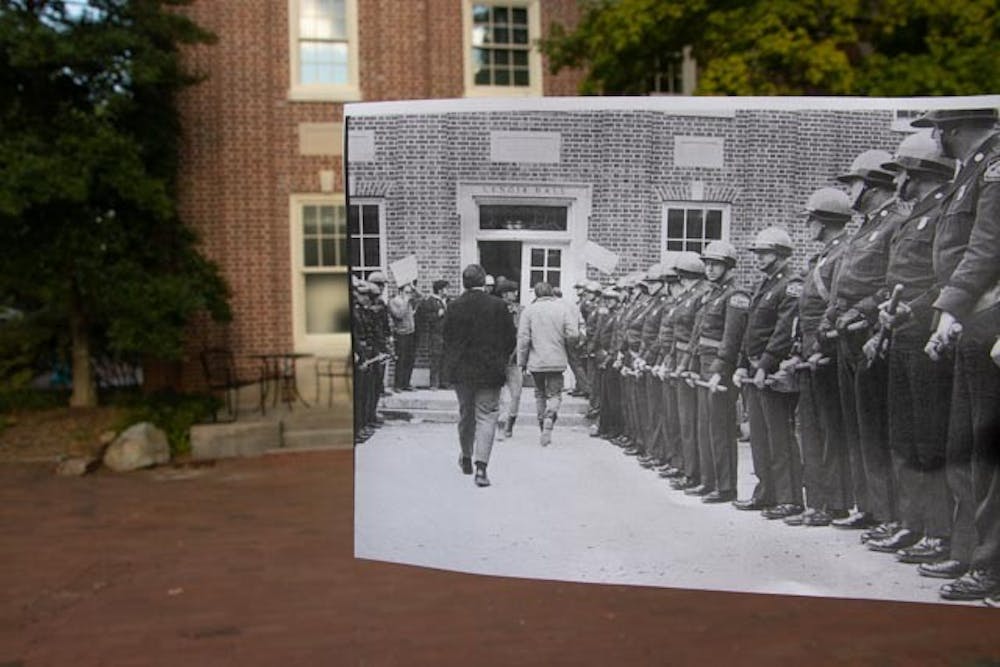

At UNC, this volatile decade culminated in the Foodworkers’ Strike of 1969. In an event that became an important part of the University’s racial and labor history, UNC food workers went on strike in search of racial and economic justice, something that even five decades later, students and employees are continuing to fight for.

Despite its nominal integration a decade before, UNC remained a disproportionately white institution. Although the census taken in 1970 showed that Black North Carolinians made up around a quarter of the state’s population, just 113 of the 13,352 students at UNC in 1967 were Black.

At the same time, nearly all of the school’s non-academic employees were Black. As the 1960s progressed, relations between the staff and their supervisors grew increasingly strained.

In 1968, several Lenoir Dining Hall food workers sent a list of 21 demands to management, which was followed by a series of layoffs and continued subpar working conditions. Workers’ hours were spaced inconveniently throughout the day, their pay was lower than what was promised and management habitually ignored the workers’ complaints.

In collaboration with the food workers, the then-new Black Student Movement compiled a list of 23 demands for University leadership. Among them was a demand to “begin working immediately to alleviate the intolerable working conditions” of the staff and to “immediately set up meetings with the employees and members of the BSM in order to outline and implement constructive action.”

In early February, then-Chancellor J. Carlyle Sitterson replied to the students’ demands, claiming that UNC had made “vigorous efforts to improve the working conditions of all non-academic employees,” and that the school “expected to continue to make efforts for improvement of the well-being of all its employees.”

According to strike leader Elizabeth Brooks' interview with the Southern Oral History Program, she had several group meetings with George Prillaman, director of food services. But, Brooks said, Prillaman “began to make promises and this went on for quite some time and he never kept any of the promises.”