For the second year in a row, the Carolina Indian Circle launched a petition for UNC to formally recognize Indigenous Peoples’ Day on the second Monday in October. And this time, they were heard.

Previously left blank on the University's calendar, Indigenous Peoples’ Day is now recognized on campus. A proclamation was issued on the recognition and that the University was built on historically aboriginal territories and Indigenous lands — but failed to include that these thousands of acres of land were stolen from native communities.

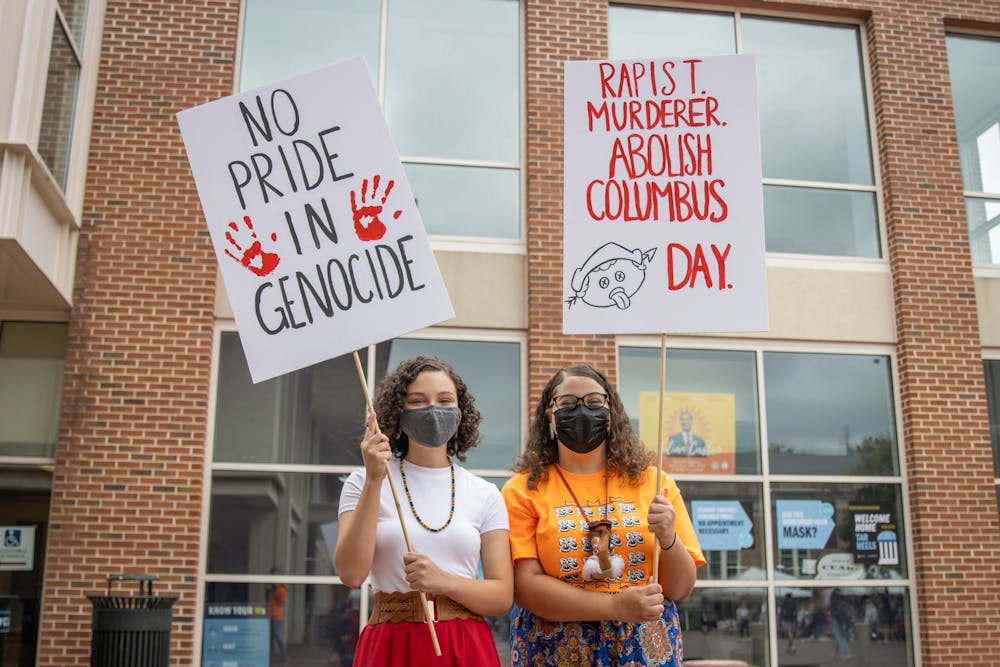

As Native American and Indigenous scholars, leaders and people with common sense have noted time and again, this land wasn’t new. Columbus didn’t discover anything and his voyage marked the beginning of a horrific legacy of genocide, slavery and colonialism. As the CIC said in their petition, “Celebrating Columbus Day is the celebration of murder.”

Nationally, the Biden Administration has chosen to continue to recognize Columbus Day alongside Indigenous Peoples’ Day, even as retailers are shying away from the former and its dark history. Under Governor Roy Cooper, North Carolina has joined the movement to recognize the day instead as Indigenous Peoples Day, though the day is still not recognized as an official state holiday.

UNC has followed suit and finally acknowledged some of its own history that it has long avoided.

While working on his dissertation in 2020, Lucas Kelley, now an assistant professor at Valparaiso University, began studying how UNC participated in a systematic campaign of selling Cherokee and Chickasaw lands in the 1800s to stave off its debts. He and colleague Garrett Wright published their findings in Scalawag, mapping out hundreds of thousands of acres of land expropriated by UNC.

According to Kelley’s research, UNC purchased dozens of parcels of Chickasaw and Cherokee lands in what we now consider Tennessee. Treaties with the Chickasaw and Cherokee nations prevented the University and other settlers from actually accessing the lands until 1816, when the federal government began forcing a series of treaty renegotiations that forced the Chickasaw and Cherokee Nations to eventually leave their lands.

This allowed UNC to actually sell the land parcels to other settlers, funding 94 percent of the University’s budget in the fiscal year from 1834 to 1835. Kelley emphasizes that these sales of Indigenous land also enabled the expansion of slavery.

“When we think about settler colonialism, it wasn’t just about seizing Native American lands,” said Kelley. “At least in the South — it was about putting slave labor camps in these areas.”