In discussions regarding the history of American civil rights, integration is sometimes treated as an instantaneous event. In popular history, Brown v. Board of Education marked the end of segregation in schools, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 ended segregation in public facilities and the Fair Housing Act ended segregation in American housing.

But a closer analysis reveals the ugly truth — American integration was absolutely not instantaneous and continues to be a work in progress. School districts have been ordered to desegregate as recently as 2016, and demographic maps of cities reveal urban environments fractured across racial lines. Similarly, the process of integration at UNC-Chapel Hill has been a lengthy one.

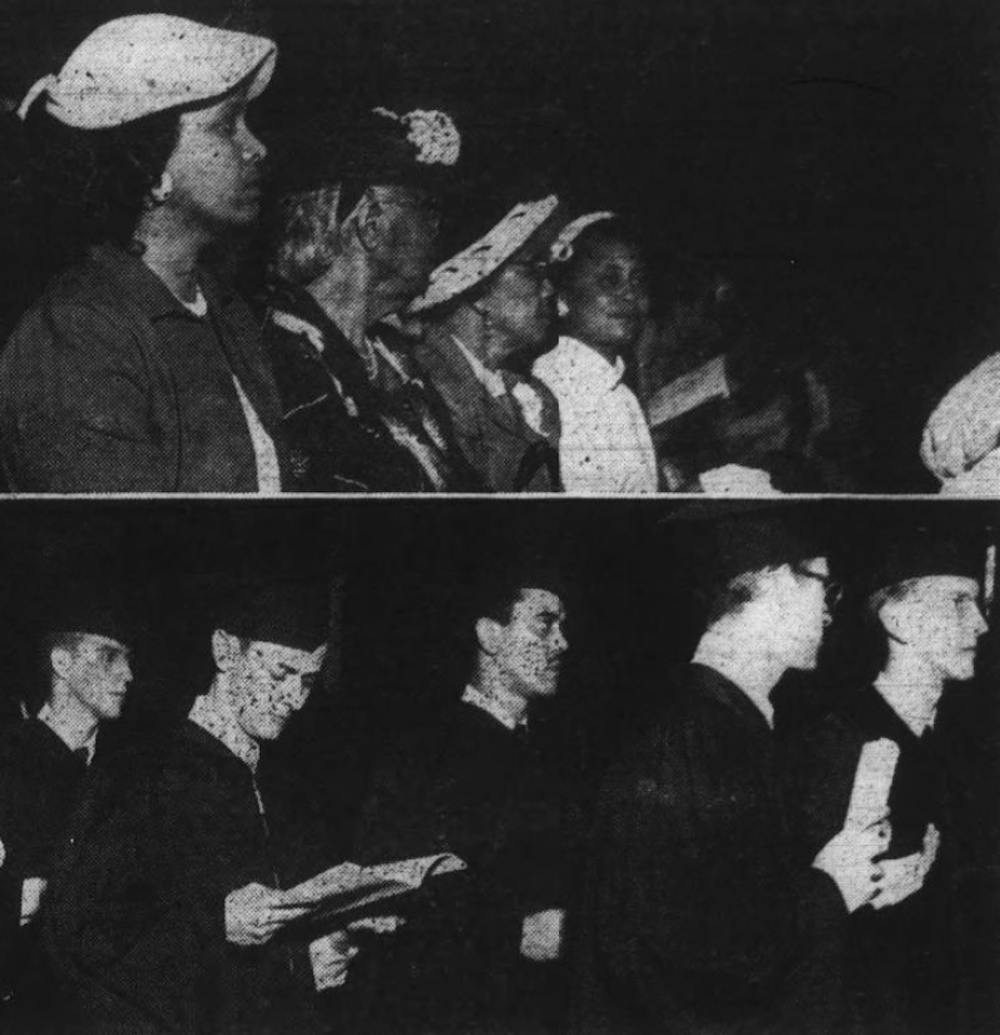

In 1951, five law students – Harvey Beech, James Lassiter, J. Kenneth Lee, Floyd McKissick and James Robert Walker – became the first Black students to enroll at UNC. Their entrance was preceded by decades of legal battles, waged by advocates for university integration, ending finally in a decisive ruling in the students' favor in Carmichael v. McKissick.

In a story repeated across the country during struggles related to integration, the men faced hostility and aggression from white students at the University. In a 1989 interview, McKissick recounted how students, “would come in and they'd put a black snake in [his] drawer,” knock lunch trays out of his hands and harass him. He also received letters from the Ku Klux Klan, warning him that he was “at the wrong place.”

Students who were sympathetic to McKissick and other Black students were berated, and McKissick oftentimes found himself to be the only Black person on campus.

Despite gaining entrance to the law school, Black students would have to wait several years to gain admission into the undergraduate program at UNC. In 1955, the first three Black UNC undergraduates were enrolled, after another lengthy court battle. Much like their predecessors in the law school, the school’s reception to their enrollment was cold.

In the September of 1955, then-student body president Dan Fowler wrote in a letter to the Board of Trustees that the majority of UNC students opposed integration. When it was announced that three Black students would enroll as undergraduates, it made the front page of The Daily Tar Heel. All three students went on to earn their bachelor's degrees elsewhere.

Further integration was anemic. Just four Black students were a part of the freshman class of 1960, and that number only rose to 18 by 1963. By 1968, the number of Black UNC undergraduate students had still only climbed to 107, increasing to 946 in 1978.

In the late 1960s, tensions over the status of Black people at UNC – both students and staff – boiled over into protests. In late 1968, the nascent Black Student Movement issued a set of demands, finding that UNC was “guilty of denying equal educational opportunities to minority group members of the local community, the State of North Carolina, and the nation at large.”