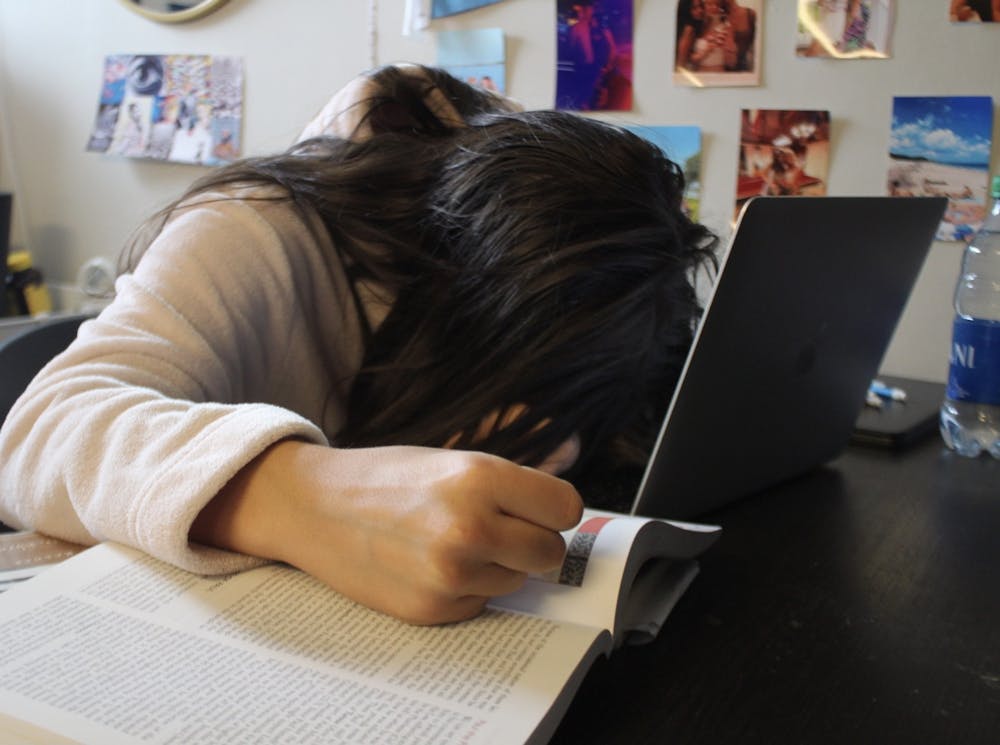

I currently have 16 tabs open on my computer browser. About half of them are Quizlets. Whenever I get bored with one set, I switch to another tab and “star” the new vocabulary I am not yet familiar with.

My General Psychology Quizlet contains terms like “glial cells," “myelin sheath” and “cognitive dissonance.” The truth is, I have a very shallow understanding of these concepts.

If my professor asked me to diagram the “myelin sheath” in class, I would probably stare at her blankly until she answered the question for me to spare everyone.

Fortunately, the exam is always multiple-choice, so all I have to do is memorize the definition. My strategy? I repeat each Quizlet card out loud until I can recite it verbatim in an eerily robotic voice.

Then, I take the assessment and proceed to forget all the information I had just studied.

I wish I could say my grades reflect genuine, deep comprehension. Most of the time, they only measure how many terms I could cram into my brain prior to the exam. That is, until the coffee high wears off and sleep deprivation fogs my memory.

It is long overdue that higher education fosters skills with real-world applications. By the time students graduate college, they should be able to effectively collaborate with others, analyze multifaceted problems and innovate solutions. Such a curriculum is far more practical than one in which students regurgitate content without understanding its significance.

In the professional world, people apply resources to problems. They rarely operate on pure memorization, even though knowing information by heart does offer some benefits.

Consider a financial consultant who solves managerial problems for their Fortune 500 client using a four-function calculator, a federal judge who interprets the Constitution without being able to crack open the actual book or a pharmacist who concocts medical cures with nothing but stored-up knowledge from an organic chemistry class.