Recently, a friend told me about how her psychologist struggled to provide proper advice that catered to her unique family dynamic.

When she discussed her mother’s lack of respect for certain boundaries, the psychologist’s solution was to simply “cut the toxicity out of her life.”

My friend decided after the session that it would be better to mend this relationship on her own, rather than pursue therapy further.

Too often, clinical psychologists engage in “victim-blaming” when their client cannot take a course of action that will immediately ease their mental distress.

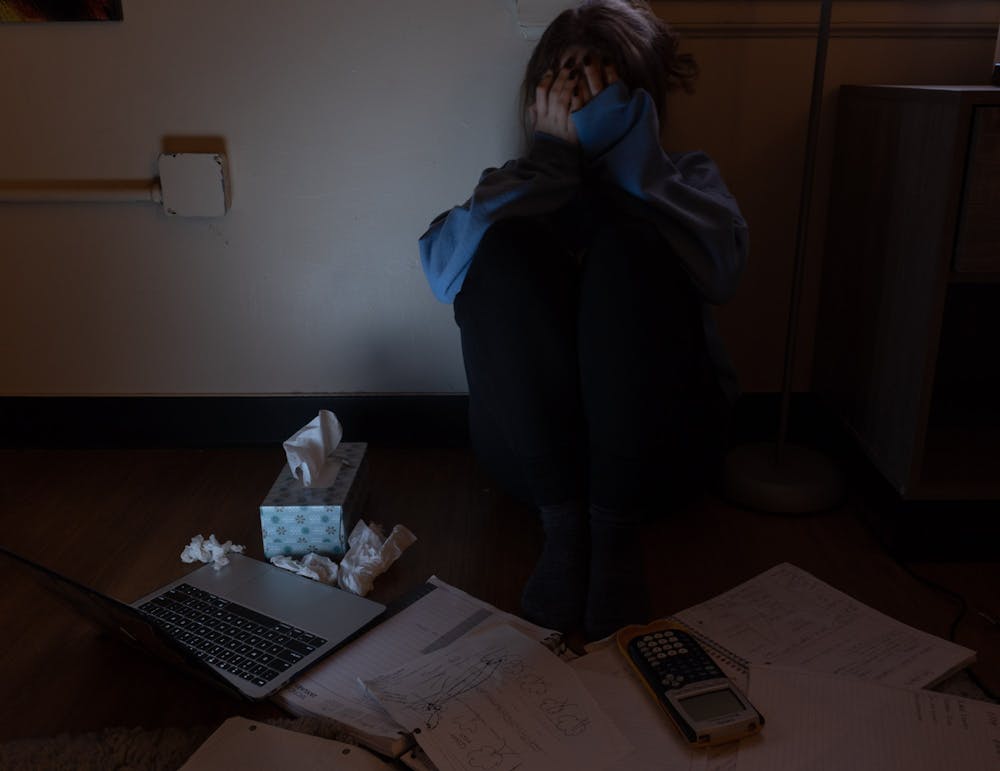

Consider, for instance, an individual who must decide between cutting off an abusive family member at the risk of facing homelessness and financial insecurity. Common situations such as this one show how “choice” is often a privilege — one that more professionals need to recognize before prescribing advice that does not work for a patient’s unique situation.

Modern data confirms that few practitioners demonstrate cultural competence. In a report published in 2016, the Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research estimated that 87.1 percent of licensed active psychologists in North Carolina are white.

And while the clinical psychology workforce has seen recent increases in racial and gender diversity, mental health resources continue to remain inaccessible for those who need them the most.

The problem is partly rooted in the ways psychologists are trained to “help” patients. In a study analyzing the relationship between social class, mental health and therapy, researchers reported that the field “has been dominated by middle-class values of liberal individualism and personal choice.”

These principles have merit, but failing to recognize how social and economic deprivation may negatively affect one’s mental health leads to problematic consequences for those seeking professional help.