It was a stormy September night, yet the roars of laughter inside the Blue Hill Event Center drowned out the winds of Tropical Storm Ian, as members of the Black Alumni Reunion (BAR) met for dinner and conversations at their first full-scale, in-person event since 2019.

The dinner was one of numerous events that took place across a five-day-long celebration of Black alumni at UNC. Sophisticated Catering and Event Planning, a Black-owned business, catered the Southern cuisine meal at the dinner.

In attendance were past and present Black UNC students, who were able to reconnect with friends, classmates, and sorority and fraternity members — who, over the years, became family, said Edith Hubbard, a UNC alumna who graduated in 1966. The reunion has become tradition; a place for camaraderie and a place for sharing experiences of joy and struggle alike.

“Shared pain, I think, tends to bring about shared kinship,” said Walter Jackson, an alumnus from the class of 1967, who was on the dinner planning committee. “There were emotional scars for almost all of us as Black students at the University in those days. Those scars don't go away easily. As a matter of fact, they probably stay with us forever. But again, the fact that we experienced those things together helped us to bond.”

The hall was filled with superlatives — the first Black student-athlete baseball player, some of the first Black female students to graduate from UNC, the third Black student to graduate from UNC with a degree in journalism. A hall full of Black Pioneers, the first generation of Black students, who attended UNC Chapel Hill from 1952 through the class of 1972.

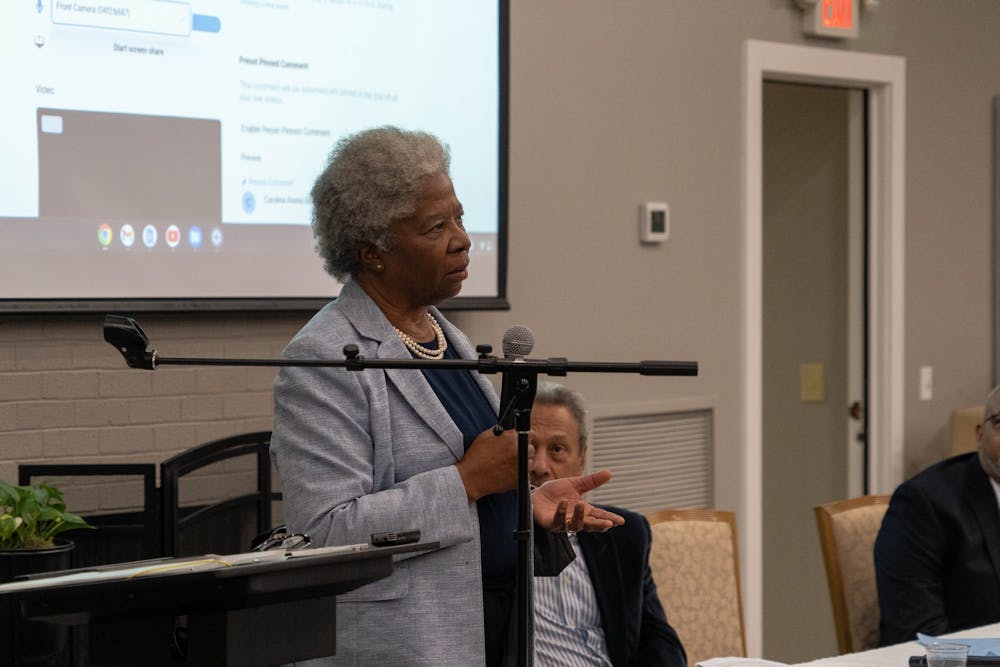

“We know that you were not the first to have the intellectual ability to succeed at Carolina, not the first to have the courage to attend here,” said Hubbard, who gave the welcoming address. “But we were the ones who were there and willing to step up when the walls of resistance finally started to give way.”

The focus of the event was a panel discussion, where alumni panelists Dr. Joanne Wilson, Cureton Johnson and former U.S. House Rep. Mel Watt reflected on their lives at UNC and how it shaped them into the individuals they are.

The first generation of African-American students experienced what Dr. Wilson, who graduated in 1969, referred to as a "culture of singularity," where they felt isolated as a result of lack of representation and respect from their white peers.

“I knew every Black student's name and family history,” said Watt, a 1967 alumnus. "But we were all scattered in dormitories throughout the campus, and each of us suffered from being alone, detached and insecure in one way or another. We were all fighting to compete and survive while dealing with a range of racial insults and trauma with no institutional support.”