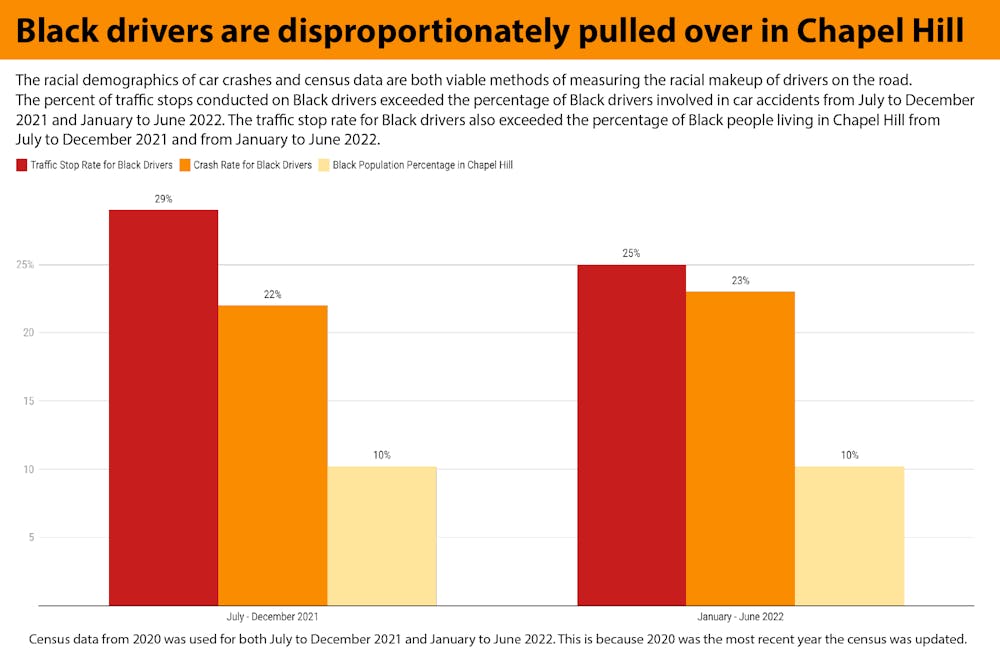

Overall traffic stop rates reveal similar racial disparities. Black drivers were disproportionately pulled over for traffic stops for the period of July to December 2021.

During that time period, 29 percent of drivers stopped were Black despite 22 percent of traffic accidents involving Black drivers.

Crash data is used by CHPD as an estimate for the makeup of drivers on the road because the people driving in Chapel Hill don't always live in Chapel Hill.

On the other hand, Frank Baumgartner, a political science professor at UNC, found that census data can serve as a rough benchmark to analyze the racial breakdown of traffic enforcement through detailed studies of traffic patterns.

Only ten percent of Chapel Hill’s population was Black according to 2020 census data.

From July to December 2021, the traffic stop rate for Hispanic drivers and the percentage of Hispanic drivers in car accidents were both ten percent. In contrast, seven percent of Chapel Hill’s population was Hispanic, according to the 2020 census. The results were similar in the January to June 2022 period.

In Carrboro, the rates of citations to warnings in 2020 were disproportionately higher for Hispanic drivers. The ratio of citations to warnings was 3.88 for Hispanic drivers, 1.56 for Black drivers and 1.47 for White drivers.

Traffic stops revealed a similar disparity. Black people were pulled over in 29 percent of the traffic stops, despite 16 percent of the town's population being Black. Hispanic people were pulled over in 12 percent of traffic stops by Carrboro police, despite just seven percent of the town's population being Hispanic.

Carrboro police reports from 2020 also show that Black drivers were more likely to be pulled over for equipment and regulatory reasons, which include expired tags or a broken taillight.

23 percent of Black drivers that were pulled over were stopped for regulatory or equipment reasons, compared to 19 percent of white drivers pulled over and 17 percent of Hispanic drivers.

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

Baumgartner's research on traffic stops found that they disproportionately affect Black drivers statewide. His research also showed that regulatory and equipment stops in North Carolina unequally affect Black drivers.

According to Baumgartner, traffic stops are often used by police officers as a legal justification to conduct a criminal investigation. He said the minute details of traffic laws mean most drivers might technically be committing some infraction at any given time.

“The traffic code is a policeman’s dream,” he said.

Internal reforms

In 2020, the Town of Chapel Hill’s Re-imagining Community Safety Task Force resolved to stop CHPD from conducting regulatory stops — a practice that Chapel Hill Police Chief Chris Blue said has already been heavily de-emphasized since 2013.

Carrboro Chief of Police Chris Atack followed suit in 2021, encouraging Carrboro police to avoid making regulatory and equipment stops unless there was an immediate threat to public safety – for example, bald tires.

He also acknowledged that traffic citations often criminalize poverty and that fines might disproportionately affect predominantly Black communities, who tend to have lower incomes than predominantly white ones.

“If you have to spend $200 in court, you may not have had $200 to fix the issue. So, now we’ve compounded the problem and made it less likely that will be corrected,” Atack said.

Both Atack and Blue said they were committed to addressing any racial disparities in policing, wherever they may appear.

The historical legacy of the police force in America makes that task difficult.

Kristie Puckett Williams, deputy director for engagement and mobilization of the American Civil Liberties Union of North Carolina, said racist attitudes permeate statewide law enforcement.

"Law enforcement originates from slave patrolling," she said.

Barbara Foushee, a Carrboro Town Council member and a member of its Community Safety Task Force, said that those values are an institutional problem that goes beyond law enforcement.

“Racism is everywhere, it’s baked into every system that we have, and policing is a system,” she said.

These attitudes are present at every level of society and affect policing in many ways, according to Blue.

He said profiling by proxy is a phenomenon where racist attitudes held by individuals who call 911 are passed on to the officers who respond.

To mitigate the issue, CHPD recently began allowing officers to ignore calls that do not contain any evidence of actual criminal activity, Blue said.

Despite the changes local departments have made, Pucket Williams said she thinks the only way to completely end over-policing is to end the institution.

But according to Foushee, there is little appetite among the local population for reductions in the police force, much less total abolition.

“Folks have become used to having the police come when they call,” she said.

Measures like affordable housing and mental health services can also be effective at reducing crime and making everyone safer, including those most disadvantaged by these systems, without involving police officers.

Blue said that in 1973, CHPD became the first department in the country to hire social workers to respond to calls alongside or even instead of police.

“Because we’ve had that unit embedded in our operations for 50 years, our appetite for a more holistic approach to law enforcement has been well established,” he said.

Paris Miller-Foushee, a Chapel Hill Town Council member and member of the Re-imagining Community Safety Task Force, said re-imagining the future of community safety has to be an integrated regional effort.

“This work needs to be done regionally," she said. "It can’t be solved by Chapel Hill doing one thing, Carrboro doing their thing — we need to come together as a collective."

@gacmorrison

@DTHCityState | city@dailytarheel.com