UNC is also working on identifying bottle filling stations across campus that filter for lead and require filter replacements.

EHS employees, student volunteers and an outsider contractor are working together to test buildings, according to a University spokesperson.

Early detection

Drew Coleman is a professor of earth, marine and environmental sciences at UNC. His team of Robeson County Early College student interns initially discovered lead this summer in buildings such as Wilson Library and South Building.

The team collected large water samples from multiple buildings for their isotopic fingerprinting research since they anticipated the levels of lead to be low.

“We weren’t expecting to find any sort of magnitude of lead,” Michael Sandstrom, a postdoctoral research associate who was also involved in the summer project, said.

Coleman said he emailed EHS as soon as he got the concerning results in early August.

The University then began investigating and conducting their own testing. The campus community was notified on Sept. 1 of the lead discovery in Wilson Library, and building occupants were told a few days prior.

“We owe a huge debt of gratitude to Professor Coleman and his team for alerting this event,” George Battle, vice chancellor for institutional integrity and risk management, said.

Coleman and Sandstrom both agreed that they think UNC has since responded appropriately in their campus testing.

Lead in drinking water is likely a nationwide problem in older public buildings, they said.

“I think UNC might be at the forefront recognizing it and bringing it to people's attention,” Coleman said.

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

Could there be legal implications?

Tom Wilmoth is an attorney with experience in toxic torts cases in North Carolina, such as the Camp Lejeune and GenX water contaminations. He said it is commonly known that buildings constructed prior to the 1980s could have lead in their fixtures.

“I think you have reasonable expectation if you go to a public university that the water is going to be safe to drink,” Wilmoth said. “And then to find out there's lead in it is pretty shocking.”

He said UNC “failed” to meet their duty to meet that expectation.

“From a legal perspective, so if you were looking at a lawsuit, then I think you have a strong negligence argument that they should have been testing that or at least aware of it prior to being told by one of their interns,” Wilmoth said.

Proving negligence would likely require proving lead exposure contributed to changes in one’s health, he said, adding that faculty or staff who have been working in affected buildings for many years or expectant mothers are the most at risk.

The University is continuing to offer free blood level testing for students and post-doctoral fellows at Campus Health. Faculty and staff can contact the Employee Occupational Health Clinic.

As of Nov. 14, a University spokesperson said 114 people have utilized the service. None have had above normal levels of lead detected in their blood.

Historic concerns

Marc Edwards is a professor of civil and environmental engineering at Virginia Tech who has studied lead in drinking water for 30 years. He has been involved in exposing lead water crises in Flint, Mich., and Washington, D.C.

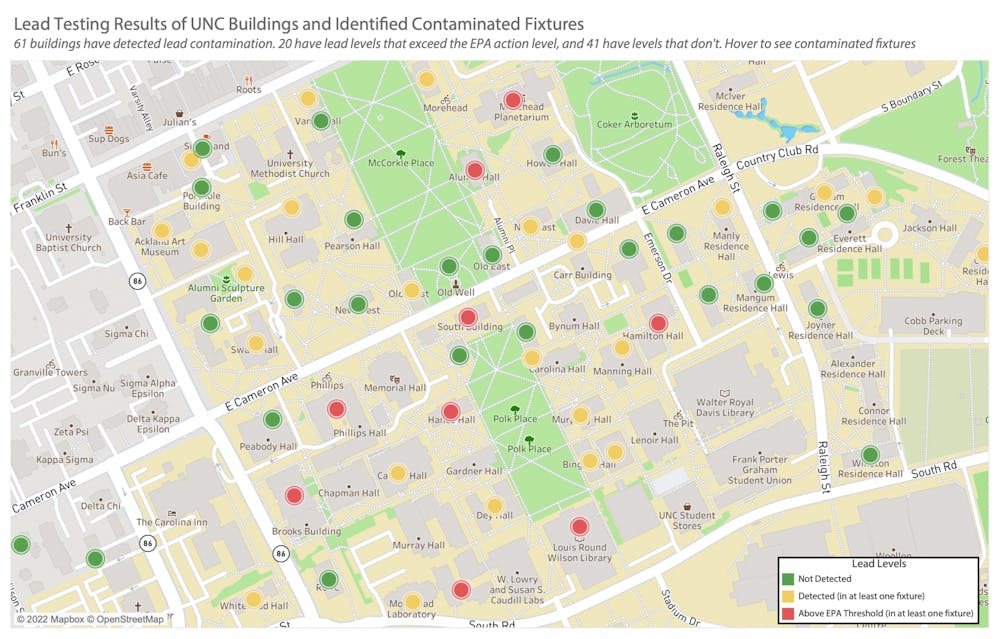

He was also involved in 2007 lead testing on UNC’s campus after the substance was found in the water of four newly constructed or renovated buildings, including the Campus Y, Caudill Labs and Chapman Hall.

“We had to roll up our sleeves and crawl into little places to figure out and to use forensic techniques to identify where the lead is coming from,” Edwards said.

The corrosion of brass plumbing turned out to be the source of lead contamination. His research led to a 2014 law which lowered the legal amount of lead in brass.

He said it can sometimes be “semi-random” as to whether a chunk of lead falls into one’s sample container. Testing a tap once does not mean there will never be a problem.

“It's a dirty secret that has largely been ignored for 20 years,” Edwards said. “I've been trying to point it out, but it's hard to get people to change their paradigm.”

@forepreston

university@dailytarheel.com