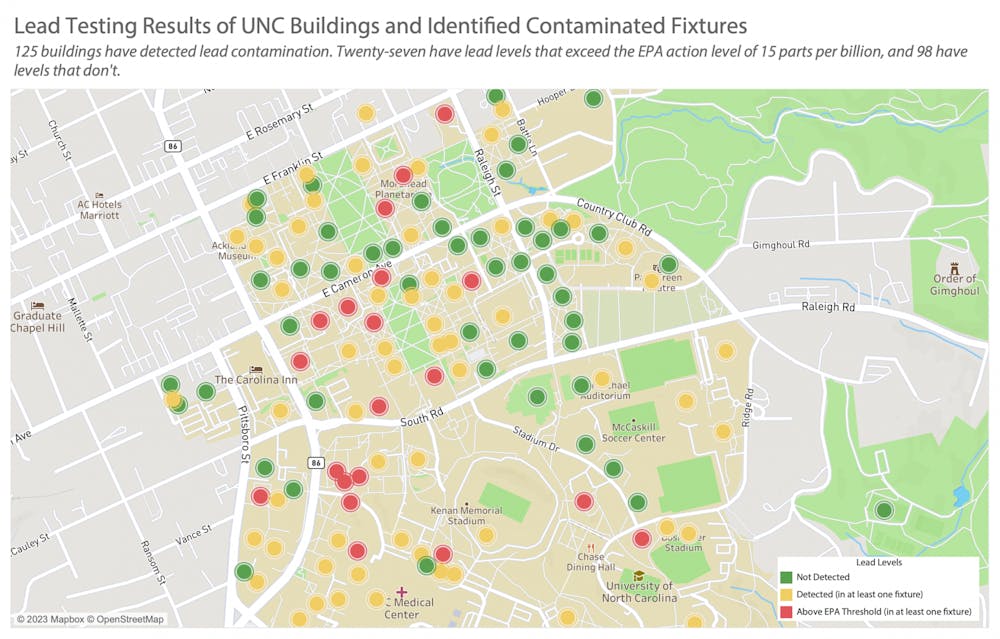

Detectable levels of lead have now been discovered in at least one fixture of 125 buildings on UNC’s campus.

Memorial Hall and the Kenan Center recently joined 25 other buildings in having samples exceeding the Environmental Protection Agency’s threshold of 15 parts per billion that require water systems to take action.

Drinking fountains in the Brinkhous-Bullitt Building, which houses UNC’s Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, have tested among the highest concentrations of lead on campus, with one sample detecting 1100 ppb — over 73 times higher than the EPA threshold.

Dozens of buildings with samples below the threshold have experienced lead in sink water, such as at recently tested Boshamer Stadium, Davis Library and the Chancellor’s Residence.

A University spokesperson said the testing of buildings constructed before 1990 concluded at the end of 2022 and will now move to phase four of the project, which includes testing of all remaining drinking fixtures on campus. Testing is expected to finish by the end of the spring semester.

According to financial disclosures obtained by The Daily Tar Heel, UNC is paying upwards of $666,800 to an outside contractor to conduct water sample testing. EHS employees and student volunteers are also contributing to the testing.

If lead is detected in any water fixture, the University said it will be immediately placed out of service and repaired or replaced.

“The remediation of drinking fixtures that tested positive for lead is an ongoing project that is currently underway,” UNC Media Relations said. “The University is remediating these drinking fixtures as quickly and efficiently as it can.”

UNC is continuing to offer blood lead level testing to students, faculty and staff who live, work or study in an affected building. Over 100 individuals have used the service, and none have received results exceeding the CDC’s reference range.