Have you ever wondered how fashion trends worked before the fast-paced world of smartphones, social media and influencers? Traditionally, trends originated from a few select fashion houses and were ruminated over by elites before trickling down to boutique windows where the average housewife would stop, stare and purchase.

Fashion was a prolonged process that lent itself to influences like the economy.

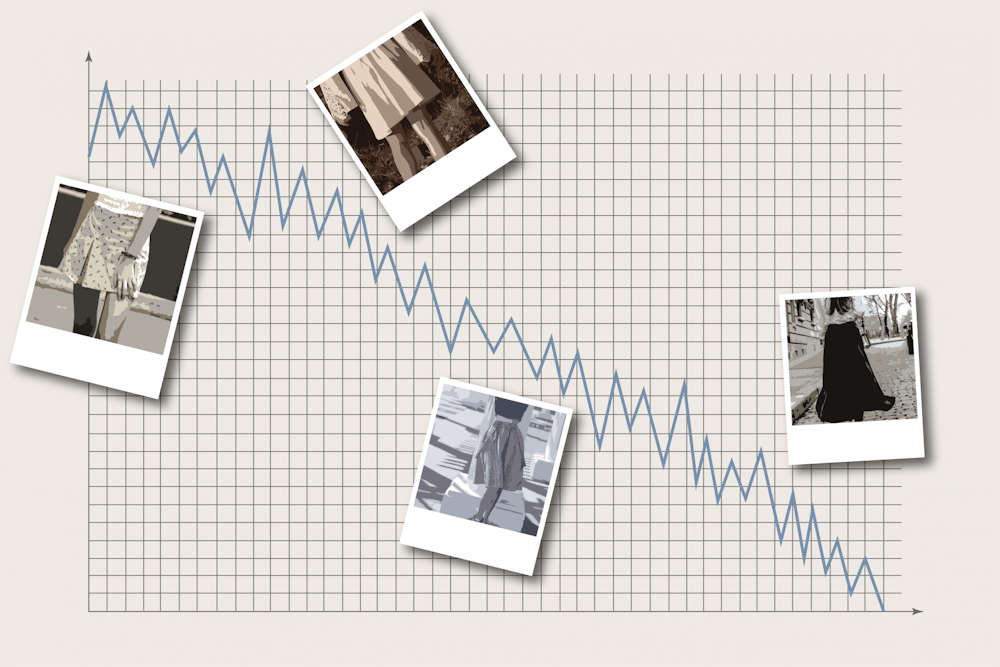

In 1926, economist George Taylor introduced the hemline index theory. He observed that, as the economy flourished, hemlines shortened and shorter skirts made their way to the streets. During periods of economic depression, Taylor noticed, hemlines tended to lengthen.

The hemline index is, at first glance, a plausible theory. In the 1920s, hemlines rose. Then, along with the Great Depression, skirts got longer. In times of prosperity, many women wanted to boast their expensive stockings, leading to higher hemlines — think flapper skirts of the 1920s and mini skirts in the 1960s.

But, dig deeper into the fashion archives, and you’ll see that the hemline index might not hold up. War, politics, pandemics and social movements influence what we wear.

In 1947, Dior dared to drop long, sweeping skirts in its spring collection. Some women welcomed the new just-in look, while others decided to reject the autocratic role of designer fashion houses, giving birth to the “Little Below the Knee Club."

The club accumulated over 300,000 members who advocated for the luxury of choice when it came to clothing. In the spirit of their name, the group campaigned for skirts that hit “a little below the knee” to remain fashionable.

In the eyes of the average American woman, long skirts alluded to the garb of the Cult of Domesticity. They symbolized the perfect picture of a 1950s domestic housewife — a loving mother devoted to raising kids and cooking meals while her husband worked to provide for the household.

Following World War II, a time when women stepped into the workforce, sentiment on the rigidity of gender roles began to slowly shift. Women were desperate for control in their everyday lives, beginning with how they dressed. Rosie the Riveter didn’t wear Victorian-style skirts, so why should they be forced to?