'Our failure to practice what we preach'

In 1934, Robert House, then-dean of administration and later a UNC chancellor, sent a letter to UNC System President Frank Porter Graham saying he was concerned about the treatment of the majority-Black janitorial staff.

The Janitors’ Association’s president, Elliot Washington, had written to House to say most of the staff was unable to join a local union because it was too expensive, even though they thought joining would “mean a decrease in the death rate of our people.”

“The enclosed letter from the President of the Janitors Association troubles me about our responsibility to the colored people who work for us,” House wrote to Graham in the letter.

During a time of progressivism in the United States following former President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, some faculty members were concerned that the University wasn’t living up to its ideals.

“Every once in a while I am disconcerted over the discrepancy between our liberalism in theory and our conservatism in practice,” Wiley Sanders, a UNC sociology professor, wrote to Graham in 1937. “Or in other words, our failure to practice what we preach.”

Workers reorganized in a different union during World War II and began to criticize North Carolina's collective bargaining law.

Martin Watkins, a student at UNC in 1946, wrote in a letter to Graham that the wages of workers were “criminally low,” and criticized the argument that the employees couldn’t use a contract to demand anything.

“We must still be reminded that the employees of the University, many of them heads of families, cannot live decently at 35 and 40 cents an hour,” Watkins wrote in the letter.

According to one union leader’s 1947 letter, many of the housekeepers during that time had to work more than one job just to afford “the bare necessities.”

'We’re not satisfied'

In 1957, a new salary plan was promoted by the University as a way to guarantee equal pay for equal work — a University memo stated some cleaning staff’s salaries might be decreased because the staff had been making more than employees at other businesses in Chapel Hill.

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

But a petition circulated in the following years claimed that other employers in Chapel Hill paid housekeepers and other maintenance workers more than the University did.

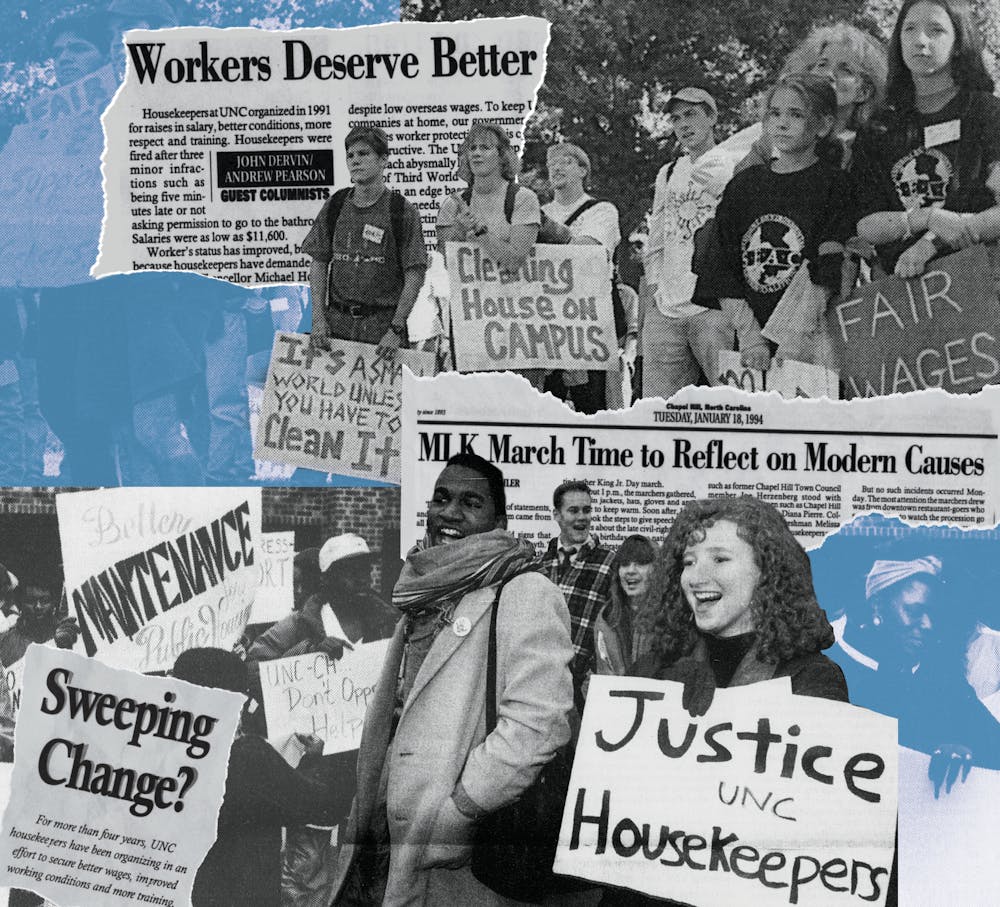

By the mid-1990s, the HKA was the driving force for organizing housekeepers on UNC's campus. It was led by then-housekeepers Marsha Tinnen and Barbara Prear.

The settlement from HKA’s lawsuit in 1996 gave each housekeeper a bonus and a raise, provided a career training program and also stipulated monthly meetings with the chancellor’s office. It also included commissions to honor African American workers at UNC and to improve housekeepers’ health.

“The victory is sweet for the Housekeepers because of the raises and the back pay,” Prear said in an NAACP newsletter after the settlement. “But in the long run, the programs the University has agreed to are more important.”

But the celebration didn’t last.

One year later, housekeepers were protesting again. This time, it was because they believed UNC had not fulfilled its end of the settlement.

“We’re not satisfied with anything that has happened this year,” Prear told The Daily Tar Heel in October 1997.

At protests in the late 1990s and early 2000s, the same demands were made — including more pay, less overtime and more vacation.

In 1999, The Workers Union at UNC advertised a march with flyers that said, “The University works because we do!”

More than 125 people participated in the rally and many stayed to take part in the union’s founding convention immediately after, where they debated and ratified a union constitution and elected Prear as the statewide president.

'Nobody should have to pay to work'

Since then, action by University employees, students and UE Local 150 members has continued on UNC’s campus. The Workers Union now represents “campus and graduate workers” alongside housekeepers.

The demands presented to the UNC System Board of Governors in January looked different because of the evolving membership in UE Local 150.

“Nobody should have to pay to work, right? That’s kind of how we’re uniting,” Dante Strobino, a field organizer for UE Local 150, said.

The demands now include an end to parking fees for campus and graduate workers, a minimum yearly stipend of $22,000 for Ph.D. students and that the Board of Governors declares its support for repealing North Carolina's collective bargaining ban.

Legislation that would repeal the ban on collective bargaining has been introduced into the N.C. House of Representatives, but Strobino said it likely won't pass this year.

He explained that the ability to collectively bargain could help housekeepers get higher raises each year than they normally do.

“It would force the University to not just say, ‘Here's 2 percent. Take it or leave it,’ right? But it's like, no, we need more than 2 percent,” Strobino said. “We're going to bargain with you until we get at least halfway right to what we deserve.”

@emilycgajda

university@dailytarheel.com