The CGA began their queer newsletter, "Lambda," in 1976, which Schultz said had one of the largest distributions of any gay newspaper in the late 1970s.

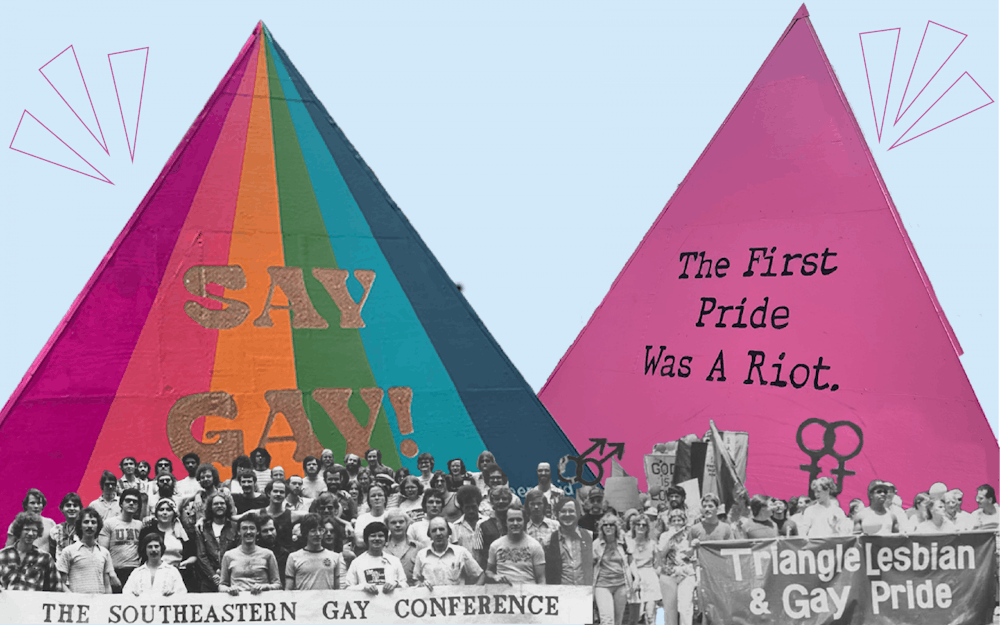

From April 2 through April 4, 1976, the CGA hosted the first annual Southeastern Gay Conference, which drew hundreds of people to the Student Union, including famous LGBTQ+ activists like Franklin Kameny.

The conference had two full days of panels and workshops on topics such as alcoholism and drug abuse in the queer community and how to pass a nondiscrimination ordinance.

"It's always fascinating to me, because things that we think of as current conversations in the queer community, these people were having in 1976," said Schultz.

1980s-1990s

In 1985, around 15 to 20 percent of UNC Hospitals' admissions were for AIDS.

Myron Cohen, global health director at the UNC Institute for Global Health and Infectious Diseases, said he began working at UNC in the early 1980s, just as the HIV/AIDS outbreak began.

Cohen described the discrimination that gay men faced during the epidemic as a "merciless stigma." Throughout this time, he said that LGBTQ+ activists were instrumental in trying to destigmatize the disease while advocating for a cure.

"And then it was these very courageous, and out there, LGBTQ advocates nationwide that accelerated the development of treatments and prevention activities and vaccine development," Cohen said.

2000s

The stigma around HIV and AIDS decreased over time as more treatments were made available, but systemic discriminatory policies against the LGBTQ+ community still existed.

In 2010, a senior UNC ROTC cadet named Sara Isaacson was removed from the program after disclosing her identity as a lesbian. At that time, the U.S. military's "Don't Ask, Don't Tell" policy banned openly gay, lesbian or bisexual people from serving in the military.

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

Isaacson said the decision to come out proactively was difficult, but she did so in order to not have to compartmentalize her identity after she was deployed or risk being outed against her will.

After coming out to her commander, Isaacson was removed from the ROTC program and the military sought recoupment for seven semesters' worth of out-of-state tuition that the army had paid for, which totaled to just under $80,000.

After the policy was repealed in September 2011, Isaacson said the UNC ROTC decided that if she returned to the program and completed her active duty commitment, they would drop the scholarship recoupment.

"There were a lot of people who felt like, or who said, that I had only come out because I decided that I no longer wanted to be an army officer," Isaacson said. "And so I felt like I needed to prove to them that once I had the opportunity to go back and commission and fulfill my obligation, that I am still a person of my word and a person of honor and that I was going to fulfill that obligation once I was given the opportunity."

Present day

This year, at the Pride Promenade, Anushka Deshmukh, a queer-identifying senior at UNC, said she feels comfortable sharing her sexuality with other people at the University.

Still, she said that she wishes there were more gender-neutral housing options on campus.

Nicole Cummings, a non-binary student in their last semester at UNC, said that queer people are often treated as an "afterthought" by the University.

Cummings said they have only learned about LGBTQ+ events, like Queer Prom, through other LGBTQ+ students, and not through the University.

"(The University) has done a lot to make sure that you feel safe, but not that you feel seen," Cummings said.

@nataliebradin | @lauren_zola

@dailytarheel | university@dailytarheel.com