Each year, the N.C. General Assembly passes a new Farm Act — a bill that creates guidelines for agricultural practices and environmental regulations in the state.

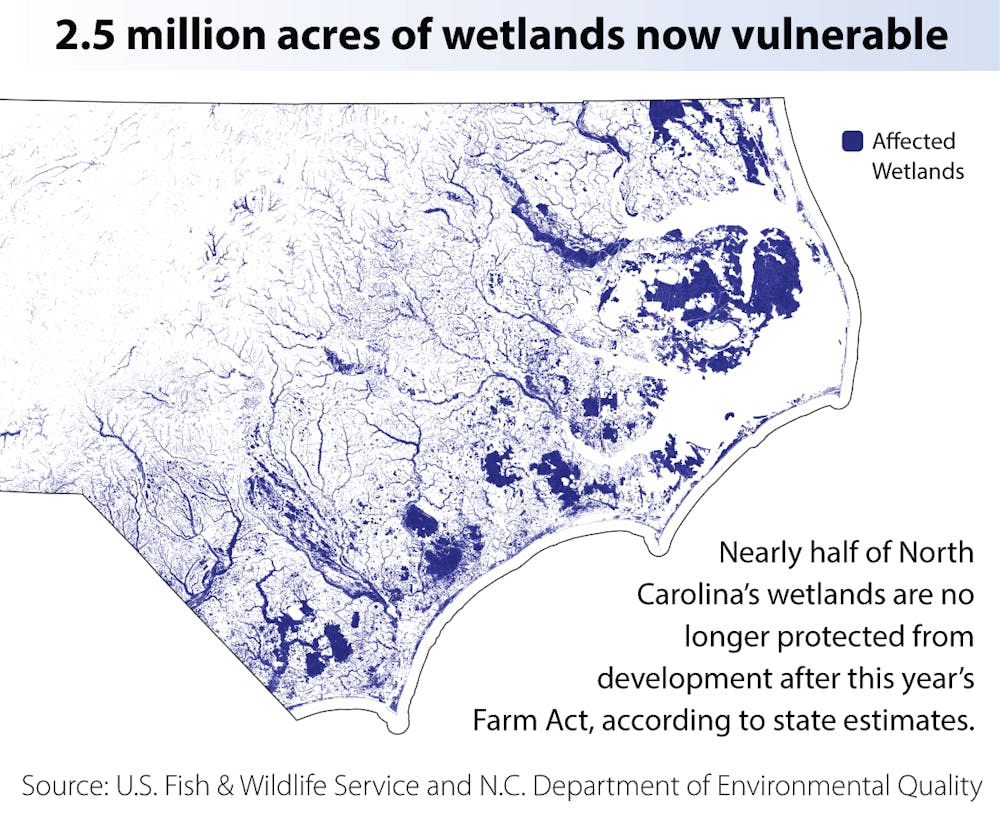

This year’s Farm Act, Senate Bill 582, included a controversial provision: it keeps the state from having to protect wetlands that do not meet the new federal definition of “navigable waters of the United States.” It was passed in the General Assembly, despite Gov. Roy Cooper’s veto, on June 27.

The new definition was established in the recent U.S. Supreme Court case, Sackett v. EPA, which was argued in October of last year and decided in May in a 5-4 decision. It changed the definition of waters of the U.S. under the Clean Water Act to only include “wetlands with a continuous surface connection to bodies that are 'waters of the United States' in their own right," according to Justice Samuel Alito's majority opinion .

The Clean Water Act provides environmental protections, like outlawing the discharge of certain pollutants and establishing wastewater standards. But it only applies to “navigable waters of the United States,” meaning a considerable amount of wetlands are now left without the protections of the Clean Water Act according to the Sackett decision.

"The provision in this bill that severely weakens protection for wetlands means more severe flooding for homes, roads and businesses and dirtier water for our people, particularly in eastern North Carolina," Gov. Cooper said in his veto of S.B. 582.

Kelly Moser, a senior attorney and leader of the Water Program for the Southern Environmental Law Center, said that after the passage of S.B. 582, only the state’s existing ban on paving over wetlands without a permit is protecting North Carolina’s communities from future flooding.

"It is completely ill-advised that the N.C. General Assembly removed those protections and that they did not allow Gov. Cooper's veto to hold," she said.

The largest swamp in North Carolina, the Great Dismal Swamp, is located in Currituck, Camden, Pasquotank and Gates counties, all rural counties in northeastern parts of the state.

"For those of us here in Chapel Hill, we see how inconvenient and scary flooding can be even in our community," Moser said. "It will be multiplied for rural communities, communities of color and lower wealth communities."