Zines evade strict definitions. They are journals with stapled and glued ephemera. They are digital collages. They are small poetry anthologies and folded pieces of paper full of doodles.

Pronounced as in “magazines,” zines are roughly described as self-published DIY booklets that feature — often underrepresented — personal, social or political expressions.

“It was, in its origins, about radical communication and dissemination of information,” zine artist and UNC alumnus SamLevi Middleton-Sizemore said. “So civil rights movements, the feminist movement, the early gay liberation movement, all used zines.”

Because of their loose definition, zines can look as experimental, professional or messy as an artist likes. Their messages, like their media, come in a variety of shapes and sizes, from music reviews to quirky satires and political calls to action.

They also provide a means for creating networks between underrepresented groups, according to Josh Hockensmith, the interim head of the Sloane Art Library at UNC, which has its own collection of contemporary zines.

“They tend to be about building communities and reaching out to people with similar interests, where you're not finding that kind of network otherwise,” he said.

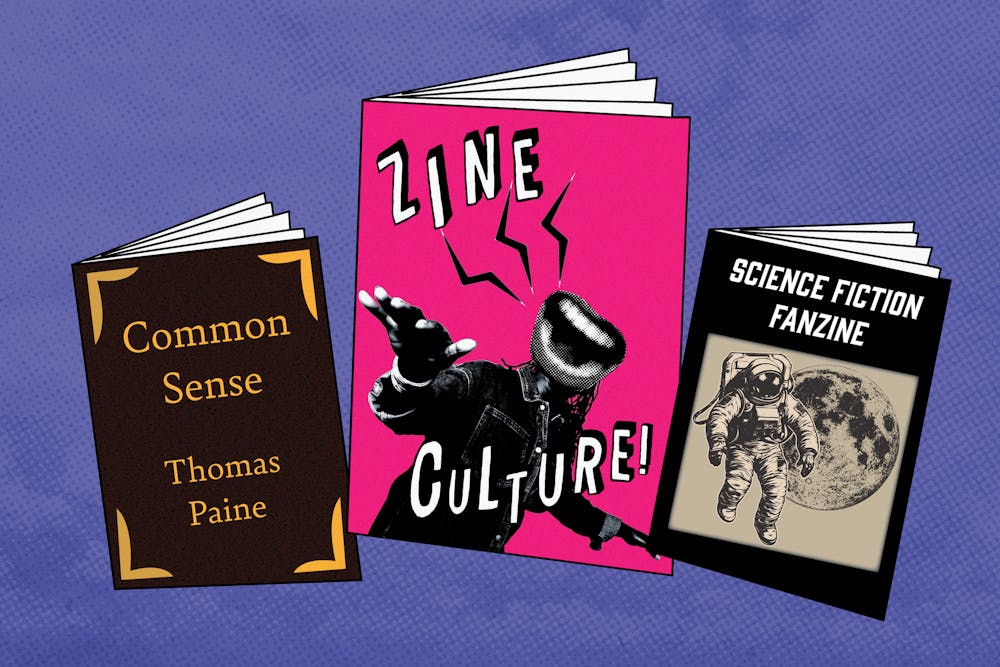

The namesake of today’s zines is the 1930s science fiction fanzine that featured sci-fi comics and letters to authors, but comparable magazines have existed as early as the 1920s through Black writers’ “little magazines” of the Harlem Renaissance.

Some even say that the idea of zines began with the publishing of Thomas Paine’s “Common Sense” pamphlet in 1776, in which Paine tried to persuade the colonies to declare independence from Britain.

Despite the ambiguity in definition, zines found a community in the 1970s, when they became a central feature in punk subcultures. The small-batch publications were where one could find local underground concerts, band interviews and the latest album reviews.