Danita Mason-Hogans, a community historian and Chapel Hill native, said people weren’t properly prepared for integration, despite the fact that the U.S. Supreme Court outlawed segregation in public schools 12 years earlier in its Brown v. Board of Education decision.

Mason-Hogans said the Black students were entering a hostile environment, and some of the white students' parents had already decided what the students from Lincoln were like.

“That they were academically inferior, that they were culturally dangerous and that they were students that their children wouldn’t mix well with,” she said.

Although more than 50 years have passed, anti-Black stereotyping and its effects still impact the district today.

In the 2022-23 school year, 332 students were suspended from CHCCS. Black students make up 11.4 percent of all students in the district but over 45 percent of suspensions.

A report published by the American Civil Liberties Union in October revealed that from 2021-23, Black students in North Carolina were referred to law enforcement at five times the rate of white students for disorderly conduct.

In Orange County, where CHCCS is one of two public school systems, only Black students were referred to law enforcement from 2017-2023.

CHCCS began its school resource officer program in 1989, but the first instance of police patrolling schools goes back at least 20 years earlier: to Nov. 11, 1969.

Mason said he could see the police arrive at the school from his classroom.

“We had tear gas thrown into our classroom, the doors locked,” Mason said. “And as I recall, we broke windows or the doors to get out.”

The DTH reported that Town police, sheriff’s deputies and highway patrol all responded to the incident and continued to patrol the school in the days following.

Along with continued inequities in discipline, research shows CHCCS has a systemic problem with achievement gaps between student groups.

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

In 2018, the Stanford Center for Education Policy Analysis published a report that used standardized test scores to measure the achievement gaps between white and Black students nationwide. The report analyzed the results of roughly 200 million standardized math and reading tests administered to public school students in several thousand school districts from 2009-2013.

According to the report, CHCCS had the second-worst gap in the analyzed data, which also extended to disparities between white and Hispanic students.

Many of the schools now have improvement plans that focus on lowering racial disparities in discipline and closing the achievement gap between different student groups.

At CHHS, part of the strategy is getting more Black students into Advanced Placement classes and taking AP exams, two goals that have seen some success in the past few years. In 2023, roughly 23 percent of Black students took an AP exam, a jump from 11.4 percent three years earlier.

Kathryn Cole, a librarian at Northside Elementary School, said she tries to incorporate local Black history into the curriculum for younger students whenever possible.

She said students are going to talk about race whether or not it's being taught in schools — the difference is creating a space for open conversation and ensuring students have accurate information.

Cole said she realized students were walking away from lessons thinking the segregated, all-Black schools in Chapel Hill were bad because they didn't have the same resources or support.

“There was still, and has always been, joy and safety and love and things of beauty, in spite of the bad,” she said.

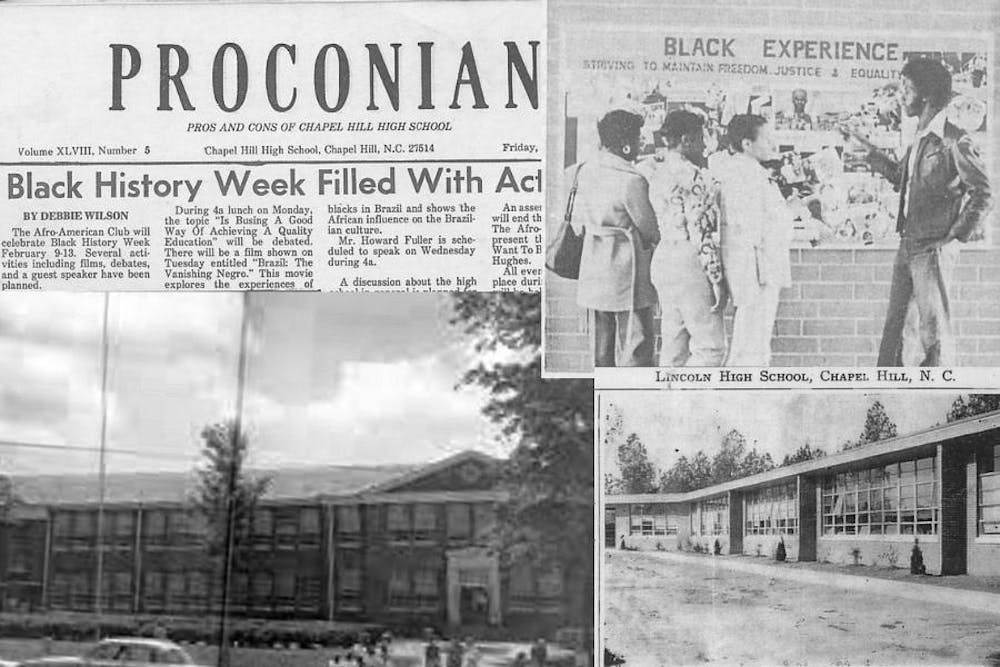

Mason-Hogans said an overlooked part of Lincoln’s history is that the school produced many brilliant scholars, despite its limited resources.

“Academic rigor was the norm, it wasn’t the exception,” she said.

Mason said, overall, the students from Lincoln wanted their traditions, artifacts and history to be valued by their new school.

He said some of their demands were slowly met, including changing the school's mascot to the one from Lincoln — a tiger — and displaying some of the old school’s trophies.

But Mason said there’s something that has stuck with him all these years: that one of the white counselors told him he’d be better off not going to a university.

He went to N.C. Central University anyway.

“The young Black kids were capable, and are still today capable, of doing everything that the white kids could do,” Mason said. “You just had to give them an opportunity. You had to let them know you believed in them.”

@fanning_sophia

@DTHCityState | city@dailytarheel.com