With the 96th Academy Awards approaching in less than a week, the anticipation is officially underway for what is arguably the most significant night in Hollywood cinema.

The nominations, unveiled in early January, opened the floodgates of annual outrage at which unexpected films made it into the lineup and which were snubbed (pour one out for “All of Us Strangers.”) At the center of the excitement, the spotlight invariably falls on the prestigious Best Picture category.

With 10 films nominated, will voters succumb to the “Barbenheimer” buzz? Will they opt for the safety of the war drama with Jonathan Glazer’s “The Zone of Interest” or push the boat out for Celine Song’s tale of love across borders in “Past Lives?” Will Scorsese finally get his Best Picture moment for his vaguely questionable “Killers of the Flower Moon?” (On second thought, Martin, maybe not for this one.) Given the wide range of nominees, one can’t help but question what accolades a film should possess to gain that coveted title over its contemporaries.

The Best Picture winners have a history of being reliably formulaic. Since the 1970s, historical films have been all the rage, with over-the-top dramas set in “foreign” lands trending in the '80s. In a contemporary sense, dramas about social issues and biopics are popular. Additionally, films about filmmaking capitalize on the egos of the cinephile voting panels (see “The Artist” and “Argo.”). Meanwhile, animated films are relegated to their own category, and the fact that the last comedy that won was the claw-your-eyes-out-devastation of “Birdman” indicates just how much the Academy cares for that genre.

What can we attribute this homogeneity to? Partly, it’s the fact that trends are naturally self-sustaining. Films of a certain creed win, so films of a certain creed are reproduced, leading to the phenomenon of the annual late-releases scathingly coined “Oscar bait.” Cue Spike Lee saying “every time someone is driving somebody, I lose.” (See 1989’s “Driving Miss Daisy” and 2018’s “Green Book,” which beat Lee's films those years.)

We might also look to who gets to vote on the nominations and how. Since 2009, a rank-based voting system has been in place in which more than 10,000 “global film industry artists and leaders” rank the nominations in order. While this system is deemed the fairest for choosing the film with the widest possible appeal, it does have the effect of overlooking rogue and potentially divisive outliers.

As a result, the most inventive movies seldom win. In, 2020 we saw a buck in the trend with Bong Joon-Ho’s historic win for “Parasite” as the first non-English-language feature to win. The bookie’s favorite had been Sam Mendes’s “1917” (a World War I drama filmed in *gasp* one take), with "Parasite" predicted for Best International Feature. However, on the night, "Parasite" scooped up both. Despite this, the Academy still fails to remove the Best International Feature category. This sends a clear message — the Best International Feature comes from non-Western nations, while the universal claim of Best Picture is largely reserved for American films.

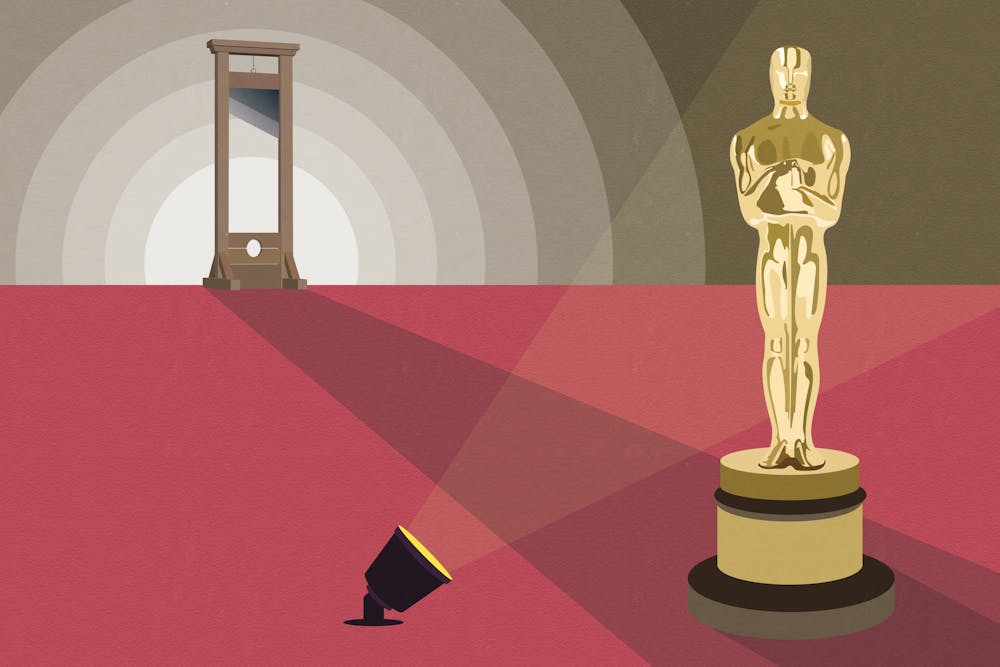

Attempting to keep up with modern globalized audiences while somehow clinging to Hollywood’s hegemonic power, the Academy can’t really decide if it’s about the United States or the entire world. Let’s not forget that this is coming from an institution established in the 1920s to increase the founder's influence over Hollywood.

When we delve into what makes a film a Best Picture, we are unfailingly met with the impossibility of determining such a title. The Best Picture winners represent a narrow slice of largely mainstream cinema which follow formulaic trends and succumb to the weaknesses of their own voting system. But somehow, despite its flaws, that iconic image of the little golden man retains its white-knuckled grip on cultural significance. To scoff at the annual ritual that is the Academy Awards does not undermine but emphasize its appeal. It’s half the fun.