In 2009, Raleigh resident Hasson Bacote was sentenced to death by an almost all-white jury in Johnston County after he shot and killed an 18-year-old during a robbery two years prior.

A year later, Bacote, a Black man, challenged this sentence under the Racial Justice Act, a law adopted in North Carolina in 2009 that allowed individuals on death row to appeal their sentences if they could prove race played a role in their sentencing, whether intentionally or not.

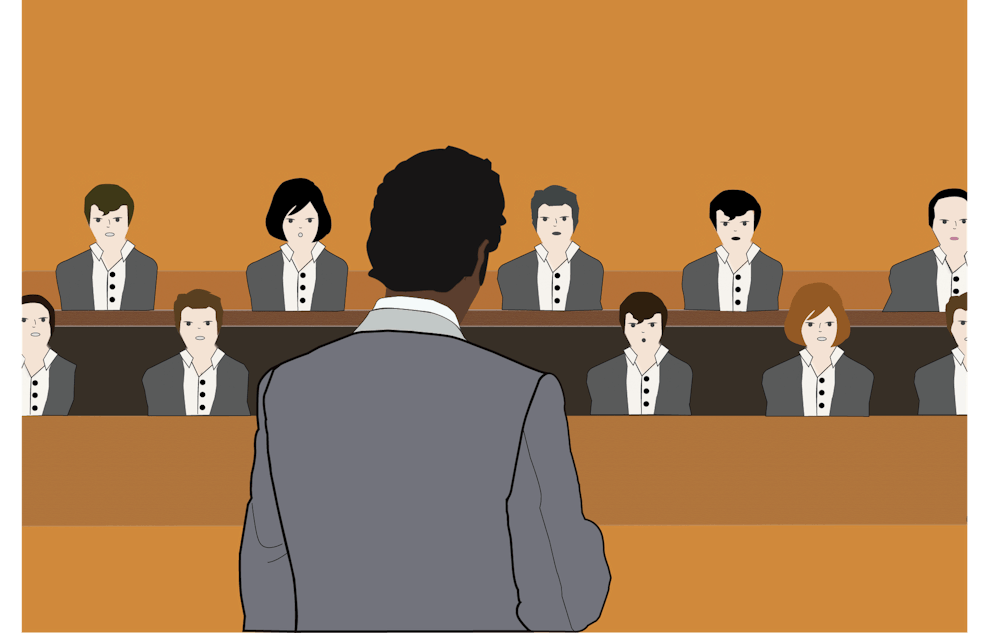

“The purpose of the law was to break the relationship between race and the death penalty,” Cassy Stubbs, director of the ACLU Capital Punishment Project, said. “And it specifically targeted three kinds of racial bias. Bias in charging decisions — who will be charged with the death penalty — in sentencing decisions — who gets the death penalty — and then also in jury selection — who gets to decide who gets the death penalty.”

Though the law was repealed in 2013 under former governor Pat McCrory, in 2020 North Carolina's Supreme Court restored full protections to those who filed claims prior to its repeal — meaning Bacote's case could still be heard.

This provision also allowed three prisoners in North Carolina to be removed from death row and be resentenced to life in prison. While they successfully challenged their death sentences while the RJA was in effect, they were placed back on death row when it was repealed.

In these cases, statewide statistical analysis revealed that prosecutors struck potential Black jurors in capital cases 2.5 times more frequently than other jurors.

Weight of Bacote's case

Court proceedings for Bacote's case began in February of this year. Historical experts and social psychologists provided evidence of Johnston County's racist past — including KKK billboards from the 1970s — as well as data from other cases within the county in which racial bias played a role.

It later became known thatBlack jurors in Johnston County were four times more likely to be removed from a jury pool. Additionally, Assistant District Attorney Gregory Butler— who served as the prosecutor in this case — was ten times more likely to strike out prospective Black jurors.