When the North Carolina football team traveled to play NYU in 1936, the Chapel Hill community thought UNC’s school system would crumble.

Angry letters flooded the desk of then-University President Frank Porter Graham, calling his decision to play the Tar Heels against an integrated football team a threat to the University.

But UNC didn’t collapse.

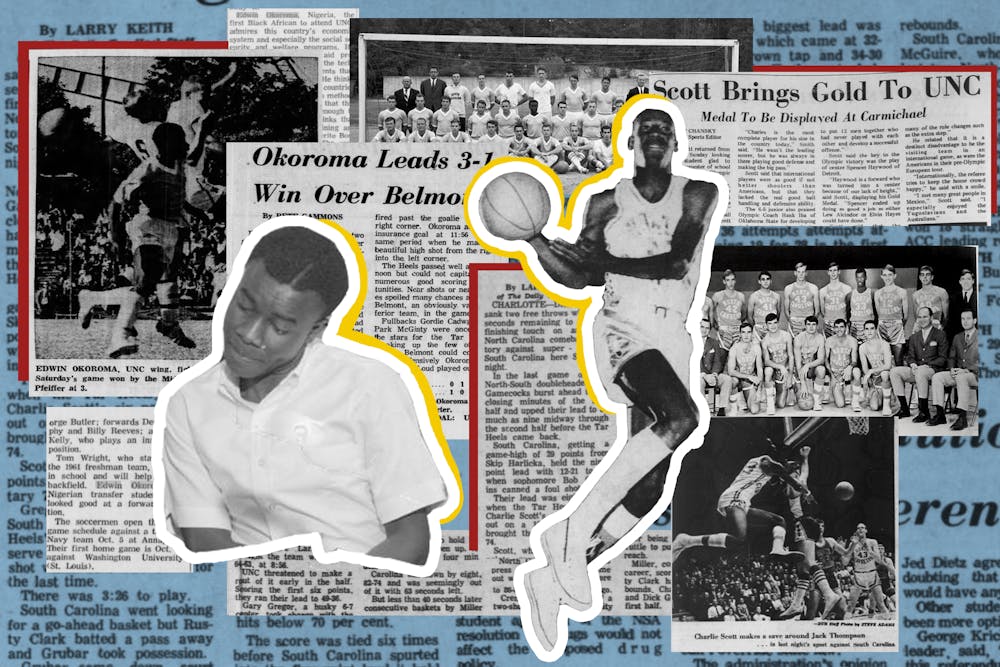

Instead, Graham’s decision made North Carolina the first major southern university to play an integrated football team, a major step toward the eventual desegregation of Tar Heel athletics and its campus. Trailblazers like Charlie Scott and Ricky Lanier later led the way in establishing racial equality through UNC athletics, while women like Frances Hogan led the charge in pushing for Title IX initiatives.

"Black athletes have an effect on American culture [that] is undeniable," sports historian and UNC professor Matt Andrews said.

In 1967, Charlie Scott became the first African American to play on UNC's varsity basketball team. At the time of his recruitment, there were only 15 Black undergraduate students and 53 in total enrolled at the University. This made campus life difficult for Scott, especially when teammates would leave for fraternity parties, or other events around town, that the star point guard could not attend during the segregated '60s.

To make things harder, his success on the basketball court determined the level of respect Scott received from predominately white Tar Heel fans.

According Andrews, Scott’s game-winner in the 1969 NCAA tournament against Davidson prompted high fives and "we love yous" from nearly everyone in the crowd. But when Scott and the Tar Heels lost in the following tournament round, the previous support abandoned him. Instead, supposed fans called him by racial slurs.

“[Only] as long as you’re one of [our players], as long as you’re successful, everything’s going to be fine,” Andrews said about the added pressure Scott had toward his performances.