Three years ago, I had immense faith in UNC. I somehow viewed the school as the beacon of diversity and commitment to one's own people. I wanted to trust that the university meant exactly what it said in its promises. But now, as I prepare to leave, I can only describe my journey here as one of initial shock, and later revelation — realizing the patterns of this administration, unchanged and unchallenged, are merely extensions of the university's historical stance.

For many, both the subtle and out-loud shifts this year feel abrupt and surprising. For me, they confirm what I've noticed over the past few years — UNC was not built for change.

I've learned that there are institutional forces driving UNC. These forces are mindsets, attitudes and, most importantly, necessary blind spots that keep the social hierarchy and political order of our school intact. UNC's administration, the Board of Trustees and various unseen entities of influence abide by an unspoken set of rules stemming from a system rooted in youthful and tolerable discrimination and marked by a pattern of forever living in the blind spot.

The Board of Trustees' 2021 tenure denial of Nikole Hannah-Jones is a significant point in the timeline of UNC. Hannah-Jones' work is founded in the simple truth of America — it was built on the back of the Black body and sustained through generational degradation. The UNC administration's choice to deny Hannah-Jones tenure for an esteemed position which typically demands tenure communicated that political attitudes ignoring such a truth take precedence in the governance and subsequent framework of our school.

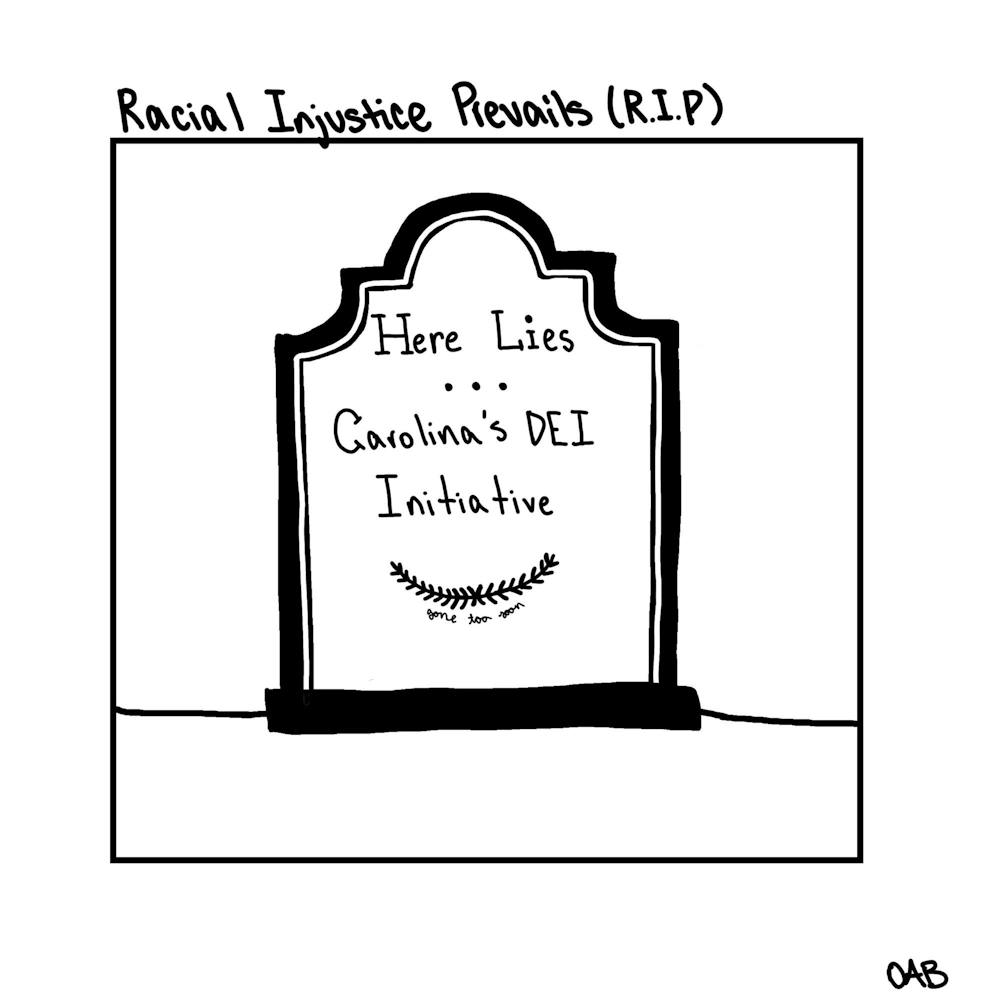

DEI initiatives are widely debated and honestly functionally flawed. Whether or not they work merits objective conversation, but their representative value is important to recognize. Their space in our environment demonstrates some vested interest in addressing proven inequities.

In late July of this year, news broke that the UNC Board of Governors had eliminated a system-wide set of positions related to diversity, equity and inclusion. Roles spared from the cuts were nicely repackaged to support other more generalized committees and offices.

Members of the BOG backed the choice, citing DEI's lack of return on investment and its component of indoctrination. The administration's choice was explained under the guise of fairness and unity. However, it more accurately reflects an unchecked power to dismiss what is not understood.

Though unrelated, both DEI cuts and Hannah-Jones' tenure denial serve as examples for an administration unwilling to reckon with its deep-seated biases. It's easy to think of these two as unrelated standalone anecdotes, but doing so ignores the symbolic nature of people hurt time and time again by the university they so earnestly put all their hopes into.

When I came in with the University's largest Black freshman class in 2021 — at 12 percent of incoming students — what I believed was a turning point for upward movement turned out to be just the opposite. Three years later, the 2024 freshman class' percentage of Black students has fallen to 7.8 percent. Numbers like these call on students to acknowledge the precarious importance of representation and how it works as a cherished value when needed.